Reducing poverty and improving wellbeing for all children: Where do we stand?

This is the first post in a 3-part series by Sharon Bessell (@BessellSharon) and Cadhla O’Sullivan (@CadhlaOSull) from the Children’s Policy Centre at ANU. Today they identify some trends from their analysis of poverty and wellbeing.

Latest data has shown that 1 in 6 Australian children under the age of 15 years live in income poverty, based on the OECD definition of poverty as households that are 50% below median income. While this is the most up to date evidence we have, it is based on pre-COVID-19 data. While Coronavirus Supplements provided during COVID-19 restrictions temporarily improved rates of poverty, it was not a permanent solution. When Coronavirus Supplements were removed many were forced back into poverty. The worsening cost of living crisis only exacerbates matters. Alongside the persistence of poverty – including stubbornly high levels of child poverty – in Australia, we have seen increased interest in wellbeing. This is part of a global shift towards economies that are driven and measured by human and ecological wellbeing, rather than GDP.

In 2023, the Australian Government moved towards new ideas about wellbeing, with the introduction of a ‘wellbeing budget’ and subsequently the Measuring What Matters Framework. While the 2024 budget was largely silent on wellbeing, work around the Measuring What Matters Framework continues in Treasury. At State and Territory levels, there has also been strong interest in wellbeing, with the ACT the first jurisdiction to introduce a wellbeing budget. The wellbeing of children and young people is a particular focus, exemplified by the Child and Youth Wellbeing Frameworks in Tasmania and the ACT.

But where does poverty fit within emerging frameworks to promote wellbeing? Are we jumping to measurement before we have clear definitions of wellbeing? Is wellbeing addressing the material core of poverty and how it undermines many aspects of an individual’s wellbeing? How child-inclusive are initiatives around wellbeing?

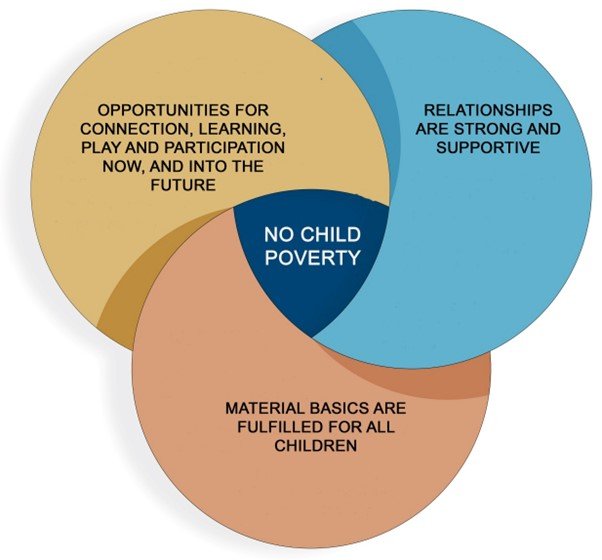

The MOR framework developed by the Children’s Policy Centre

At The Children’s Policy Centre at the Australian National University, through our More for Children research, we have been analysing indicators of poverty and wellbeing both within Australia and internationally. We accept that that no one measure of poverty or wellbeing can ever be perfect, but there are some concerning trends or patterns that have emerged from our analysis. These concerns need to be addressed if we are to tackle the disturbingly high rate of child poverty in this wealthy nation. We need to address the material core of poverty to scaffold wellbeing for all children. Here’s what we found.

Trend 1: Lack of acknowledgement re the link between poverty and wellbeing

At the Children’s Policy Centre we have developed the MOR framework, with the aim of understanding, assessing, and responding to poverty in a way that is child-centred. Within this three-dimensional framework, the material dimension – income, goods and essential infrastructure – supports the opportunity and relational dimensions.

Children have told us that when the material basics (such as having enough food and a safe place to live) are lacking, their opportunities are limited, and strain is placed on those relationships that they value most. Poverty must be addressed in order to scaffold wellbeing for all children, and yet in many Wellbeing Frameworks and Strategies, the issue of poverty is largely absent. This silence cannot continue if we are to foster the wellbeing of everyone and ensure no-one is left behind.

Trend 2: A lack of child-centred indicators/ ‘the missing middle’

More for Children highlights that children’s experiences of poverty are different from those of adults. In our research children have shared the pain created by poverty, and the ways in which their lives are impacted. Yet children are rarely consulted on matters that affect them most. This is particularly true for children in middle childhood (typically 6-12 years). The absence of child-centred indicators is evident in our analysis, with most indicators of wellbeing for children in middle childhood revolving around school. While school plays a vital role in children’s wellbeing, their lives are about much more than school. Children tell us about the importance of community, connection and relationships – and they tell us how poverty very often undermines these important aspects of their lives.

Trend 3: Changing the narrative on poverty and wellbeing

We have heard from children that they need opportunities for learning, connection, participation and play. They need strong and supportive relationships to enhance their wellbeing, but they also need to have their material needs met to expand their access to opportunities and to ensure relationship are not under pressure. We hear from children and their families about the pain and stigma that is often attached to living in poverty – just as we hear about the love and strength within families. Strategies and frameworks aimed at improving the wellbeing of people need to recognise the ways in which structures and systems create and exacerbate poverty. There is a need for systems to be accountable for reducing – and not deepening - poverty. There is also a need to shift narratives that blame individuals to a focus on challenging structural inequality and putting supports in place that ensure that the material needs of all families are met, in order to scaffold their wellbeing and create opportunities and strong and supportive relationships for all children.

Where do we go from here?

Our research with children, combined with the analysis we have conducted on wellbeing and poverty indicators, shows the importance of listening to the lived experiences of children and their families, before jumping to set domains, measurements, and indicators. When we listen, the indicators that will reveal most become clear. We also need to move beyond listening, and take the necessary action needed to end child poverty so we can scaffold wellbeing for the more than 760,000 children living in income poverty in Australia, who cannot afford to wait.

The next two pieces in the series will explore some of the trends identified above in more depth.

Content moderator: @DrSophieYates