Reasserting the public interest from Australians' kitchen tables

The “business as usual” lobbies are co-ordinated, cashed up and have a highly sophisticated mechanism to spring into action whenever a whiff of reform is in the air, writes Emeritus Professor Robert Douglas from the National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health at Australian National University in this piece from The Conversation.

Looking at "kitchen table" initiatives from the past and present, he asks whether Australia needs a new non-government structure to coordinate debate and act on a range of pressing issues in the public interest.

Grassroots common sense and decency lie at the heart of two growing movements to reassert the voice of the people in the management of our local and national affairs. Kitchen table conversations and community organising could perhaps help to reinvigorate Australian democracy.

We need to ask: who speaks for the “public interest", shorthand for the welfare and wellbeing of the general public?

The interests of the giant corporations and the mining industry are well articulated and lobbied. For various reasons, our representatives listen assiduously to them. But who speaks for the future welfare and wellbeing of our children? We need to invest in both kitchen table conversations and community organising to restore some balance to the political equation.

Pioneering successes in Australia

SEE-Change ACT recently sponsored a “Kitchen Table Conversations” workshop led by Mary Crooks, the executive director of the Victorian Women’s Trust. The trust has been influential in three programs that have successfully employed this model in recent years.

The Purple Sage project in 1998 resulted in 800 groups across Victoria meeting to discuss their aspirations and concerns about what was happening in that state, then under the leadership of Jeff Kennett. Some commentators have concluded that the Purple Sage discussions played an important role in the Kennett government losing what had previously been considered to be an unloseable election.

The Women’s Trust then modified the method to explore water policy. The Watermark team worked with water experts to produce succinct summaries of the technical issues. These were used by hundreds of groups across Victoria who met on several occasions and fed their conclusions back to the team.

People from thousands of households around Victoria were thus involved in active discussions about water policy. This resulted in a community-owned, state-of-the-art report, which has influenced policy around Australia.

Then, last year, the electorate of Indi in Victoria embarked on a kitchen table campaign to focus attention on the genuine concerns and aspirations of the people, as opposed to the issues that federal politicians were promoting. This was the election that brought out Cathy McGowan as an independent candidate. She won the seat with a swing of 9% against Liberal frontbencher Sophie Mirabella in an election that elsewhere the Coalition won handsomely.

How does the kitchen table model work?

The kitchen table model is a process in which a volunteer host invites eight or nine people. They spend two or three hours in a discussion around either a general or specific question.

There are a few basic ground rules. Everyone gets to have their say and the group listens with respect, whatever their views on the subject. A scribe prepares a summary of the discussion, which is passed on to a co-ordinating group.

The conversations may take place in homes, cafes or clubs. They may be among neighbours, friends or acquaintances. The question that drives the discussion can be as broad as “What is important to you about the next five years in Canberra?” or as narrow as “How do you respond to this two-page summary about current Australian policy on irregular boat arrivals of asylum seekers and refugees?”

These are socially enjoyable discussions that involve people sharing themselves and becoming empowered by their enhanced understanding of the issue and the views of their fellow participants.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OpOkVeY_d0&w=560&h=315]

The Latrobe Valley is one of many communities to adopt the kitchen table model.

Tackling the imbalance of power

In a 2010 book, Blessed Are the Organised: Grassroots Democracy in America, Jeffrey Stout wrote:

The imbalance of power between ordinary citizens and the new ruling class has reached crisis proportions. The crisis will not be resolved happily unless many more institutions and communities commit themselves to getting democratically organised and unless effective vehicles of accountability are constructed at many levels of social complexity.

Stout’s comments also apply to Australia today.

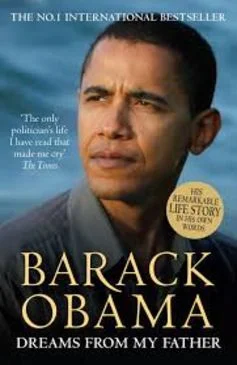

Barack Obama devoted nearly one-third of his memoir, Dreams From My Father, to what he learnt as a Chicago community organiser.

Community organising has been an identifiable profession in America for decades. Barack Obama began his working life as a community organiser in Chicago. The central feature of community organisation is the brokering of alliances between organisations such as faith groups, trade unions, schools, environmental advocacy and civil society groups.

The organiser helps to build trust across groups through facilitated dialogue sessions. The alliance acts as a public interest group to lobby governments on issues of broad public concern.

The Sydney Alliance is Australia’s most developed example of this kind of community organising. It has three full-time organisers and is beginning to make waves on issues of state and metropolitan importance.

Many organisations including NGOs, faith groups, unions, environmental groups and professional lobbies claim to speak for the welfare and well-being of the general public. But they seldom speak with one voice and pool their resources to effect or oppose policy change with anything like the single-mindedness of, for instance, the Business Council of Australia (BCA). Groups like the BCA play a key role in defending the interests of the corporate sector.

Perhaps Australia needs a new non-government structure to coordinate debate and act on a range of pressing issues in the public interest. The “business as usual” lobbies are co-ordinated, cashed up and have a highly sophisticated mechanism to spring into action whenever a whiff of reform is in the air.

Community organising and kitchen table conversations could perhaps provide the infrastructure for a future Public Interest Council Of Australia.

Bob Douglas is a director of Australia21 (www.australia21.org.au) and a member of SEE-Change (www.see-change.org.au). Both groups are developing kitchen table initiatives and Australia21 is exploring structures that could better articulate the public interest.

This article was originally published on The Conversation and is re-posted with thanks.

Read the original article.