Justice, parents and child protection: a role for a Charter of Rights?

We spend a lot of time as a local, national and global community considering the wellbeing of children and what is in ‘the best interest of the child’ when they are at risk of abuse and neglect. We spend much less time considering the rights and responsibilities of parents and other family members who have children in the care of child protection services.

It is time for a Charter of Rights for Parents and Families, argues Sharynne Hamilton from the University of Western Australia.

This week as I was doing my tax return, I did so with the knowledge that I have obligations through the “Taxpayer’s Charter”, to be honest in my declarations, to keep accurate records, to meet due dates and to generally be courteous and respectful in any interactions I may need to have with taxation office workers.

In return, I know I have the right to be treated fairly, to be provided with assistance should I need it, to have my privacy and information respected and the right to review should I disagree with decisions being made. Many organisations, notably financial organisations, have charters outlining consumer rights and responsibilities. Good. Sounds fair and something we should expect in all interactions with service providers, particularly “public service” providers.

Unfortunately, throughout my career in both research and community services I have often witnessed public service providers ignoring the rights of people from all walks of life. The most glaring lack of rights though, has consistently been for parents who have had, or are at risk of having their children removed by child protection services. “Who cares; they hurt their kids?” you ask. We expect that child protection services have intervened in the life of a family because children have been harmed or are at imminent risk of harm. No-one would deny children’s safety should be the number one priority. This does not negate, erode or otherwise deny the rights of parents and family members to be treated with justice and respect.

Our research has revealed parents become profiled very early on in the child protection process. A parent who displays any kind of negative emotion during the process of a child protection intervention can be labelled: ‘uncooperative’, ‘aggressive’ or ‘difficult’. Labels which can influence decisions being made in a courtroom. In my community service work, I rarely observed consideration that the parent may be highly distressed that their children could be taken away by strangers from a government department (often accompanied by police) at any time.

I observed parents who deeply loved their children regardless of their parenting abilities. I observed parents impacted by stress to the point where it makes it difficult to listen and then to comprehend what is being said. I observed parents who potentially had a cognitive disability. I observed parents who gave up. And I observed many parents who had experienced great harms in their childhoods from their own experiences of growing up in State care. These parents battle a complex statutory system with derisory legal representation and little support and advocacy.

During a child protection intervention, consideration should be given to the well-known and serious negative impacts of growing up in State care such as those described in the Bringing Them Home Report into the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children:

Consider the apologies to the members of the Stolen Generations, Forgotten Australians and Forced Adoptions. Kevin Rudd said in his apology to the Stolen Generations, “the injustices of the past must never, never, happen again” and Julia Gillard to Forgotten Australians: “A turning point for governments at all levels and of every political hue and colour to do all in our power to never let this happen again.” In my view, treating parents and family members in ways that give them the most robust opportunity to put their case forward and engage constructively with solutions, are a part of both taking responsibility for these past harms and ensuring that future harm for children, families and communities is minimised.

Rights charters for consumers are, in and of themselves a ‘right’. They are important. They offer tools for encouraging shared obligations, for working together toward a mutually beneficial result. When interacting with a person who is traumatised, or perhaps has a cognitive disability, charters provide a clear and constructive way to assist toward good outcomes. A charter would almost certainly be a way to meaningfully empower parents and family members to actively contribute to decisions which affect their lives and those of their children.

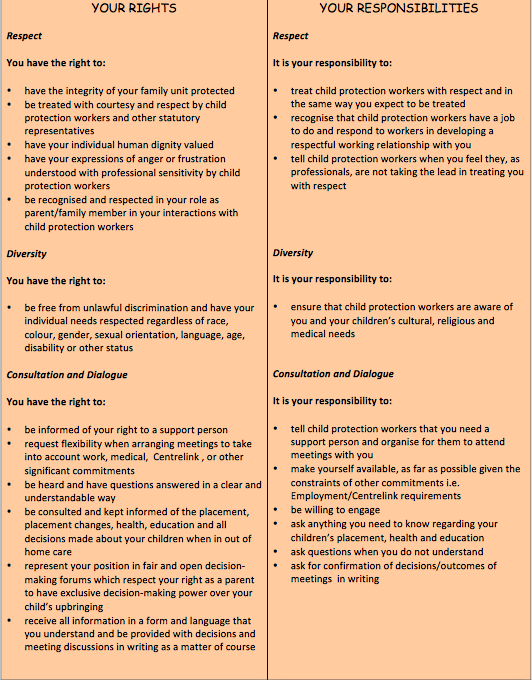

Could a charter which lays out the rights and responsibilities of parents improve the experience of a child protection intervention for all parties? In consultation with parents, family members and community members, we developed a Charter of Rights and Responsibilities for use in the child protection sphere: which sets out basic principles for operating within a culture of respect. Being guided by a charter could lead to decision-making forums in which family problems which deem children at risk can be resolved even before children are removed. It could help to ensure that all parents are treated with kindness and respect, communicated with transparently, and heard and included in decision-making about their children. It would help parents understand their responsibilities and obligations in a structured and informed way.

It would be my hope that child protection services commit to the idea of a charter of rights and responsibilities for parents and family members and implement a charter which explicitly states the rights and responsibilities or obligations of everyone involved. Children deserve to have all parties working together to ensure their futures are better. Parents and family members matter. They matter to their children, and they should matter to us.

Next year when I sit down to fulfil my responsibilities to the Taxation Department, I would like to do so not only with the knowledge that my own rights are protected through this process, but with the knowledge that a Charter of Rights and Responsibilities for Parents involved with Child Protection Services is being considered by governments around the country.

Sharynne Hamilton is a Ngunnawal woman, a PhD Candidate at the University of Western Australia and a founding member of the Family Inclusion Network in Western Australia (FINWA).