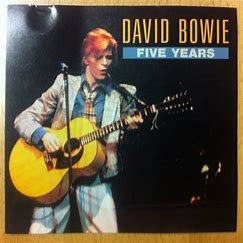

When 5 years is too long (with apologies to Bowie)

In today’s post, moderator @simonecasey laments delays to reform that mean fundamental changes to how people are treated when they are looking for work are still too far away.

It is now more than certain that the current Workforce Australia contract will continue for the original contract period of 5 years. I was trying to think of a metaphor for my ruminations on the state of employment services and Bowie’s song title came to mind. The song expresses dread at the inveitability of apocalypse in the eponymous 5 year period and serves as an earworm to remind us how much longer reform is likely to take.

We've got five years, stuck on my eyes

Five years, what a surprise

We've got five years, my brain hurts a lot

Five years, that's all we've got

The Workforce Australia model of employment services is now in its third year, and the need for comprehensive reform in Australia's employment services sector remains as urgent as ever. Despite hopes for significant change that the recent House of Representative Inquiry triggered amongst those of us who had some optimism, it appears that the current contract will run its full five-year course, leaving many to question the government's commitment to addressing the systemic issues plaguing the system.

It is more than disappointing that structural reforms to employment services such as the re-introduction of a national employment services that were mooted by the Julian Hill headed inquiry have been shelved, presumably because of the impending electoral battle in which support for unemployment has rarely been considered a vote winner and the culture war that’s constraining the scope of reforms.

What we did get out of the HoR Inquiry were some iterative initiatives announced in the Budget 2024-2024 that make adjustments to quality monitoring and mutual obligation settings in employment services. These include a review of the complaints process, increases in the resolution period for payment suspension, and adjustments to enforcement rules for first offences, attendance at appointments while working, and fully meeting requirements exemptions.

All of these are common sense changes, that will be phased in gradually over the coming months, but they are also indicative of some of the nonsensical arrangements that have made people’s experiences of employment services so punitive, and clearly show that the system has been stacked against people’s rights for so long. It is not a long bow to compare how mutual obligation requirements and their enforcement evolved under the same anti-welfare rhetoric rubric that the Robodebt Royal Commissioner called out. How much of it all do we really need and how much does it all go towards helping people actually get jobs? Very little actually as most of the academic literature shows.

Meanwhile, the everyday experiences of those navigating employment services system reflect a disturbing reality. Social media platforms are rife with accounts of disrespect, arbitrary decision-making, and a lack of genuine support. Common grievances include appointments set without adequate notice and payment suspensions used illegally to coerce people into providing pay slips.

These issues are particularly concerning given the current economic climate. With unemployment rates creeping up and the cost of living growing exponentially with the housing crisis, more Australians are finding themselves casualties of macroeconomic policy settings and fronting up to ineffective and harmful unemployment services. The system's shortcomings are thus affecting an ever-growing portion of the population.

As the number of long-term unemployed individuals increases, providers are under pressure to achieve positive outcomes with limited resources. Job advertisements for employment services positions suggest little change in qualification requirements or wage offerings, indicating a lack of investment in developing a skilled workforce capable of supporting those facing long-term unemployment. In fact, the job agency reviews show a worrying use of bonuses to top-up base wages, and a woeful lack of training and support for the workforce.

There is another post on Indeed in which a former employee of an employment service provider boasts about how they earned $1600 per month in bonuses. $1600 per month is almost $20k on top of what Indeed indicates is on average about $64k per annum.

The use of performance bonuses to supplement wages is a clear indicator of the pressure placed on individual employment consultants. This practice, known as "triple activation" in academic literature, has been criticized for prioritizing short-term job placements over sustainable, long-term employment outcomes. And when this leads to the shonky or sharp practices that have been identified in the media time and again, little is done to stop it from happening again because the whole system design enables it.

Despite the compelling need for reform, significant changes to the employment services system appear unlikely before 2027. The recent Disability Employment Services (DES) tender is set to lock-in outsourced arrangements for at least another three years, further delaying any substantial overhaul of the system.

While comprehensive reform is delayed there are steps that can be taken to improve the current system:

1. Strengthen the Complaints Initiative to ensure job seekers have access to fair and timely resolution of issues

2. Continue to push for more rational policy settings that prioritize genuine employment outcomes over arbitrary targets and surveillance of job search through points-based activation.

3. Implement real-time monitoring and accountability measures to address provider misconduct promptly.

4. Invest in the professional development of employment service staff to better support job seekers, particularly those facing long-term unemployment.

If all of this sounds like it has been said before, that’s because it has. It’s hard to find anything new to say when for nearly thee decades now the failed privatisation experiment has inflicted suffering on people relying on unemployment payments. There was a moment when I was optimistic there would be short term changes, but 5 years is far too long to hope for change.