Stop Calling it the 'Sharing Economy'. That isn't what it is.

As we look for new ways to collaborate and adopt 'disruptive' models of practice we need to be aware that just because it is disruptive, it does not mean that it is truly 'sharing' or revolutionary. The term 'sharing economy' is being co-opted as outlined in this post by Olivier Blanchard, which was originally published here.

It’s known under a number of names: The Sharing Economy. The Collaborative Economy. The Gig Economy. Because of its “fresh” and “disruptive” model, undeniable financial incentives in the middle of a global economic recession, and its integral connection to the tech startup community, this new business movement has been garnering a whole lot of attention in the last few years. If, like me, you spend quite a bit of time interfacing with tech companies and digital business professionals, you can actually feel the peer pressure pushing you to support companies like Uber, Lyft and AirBnb. If you don’t, your peers are likely to look at you a little sideways, cock an eyebrow, and find a roundabout way of asking you what’s wrong with you. If I look at this with suspicion, I’m old school. I’m stuck on old paradigms. I need to get with the times, right?

“It’s evolution, man. Business Darwinism happening right before our eyes!”

Well… no. I’m not exactly a conservative when it comes to tech or business, or pretty much anything. I’m cautious, sure, I tend not to be an early adopter (first generation tech is too buggy for the price, thank you very much), but I’m not a progress-averse curmudgeon. Far from it. I just like to understand stuff before I buy into it. That’s how I avoid falling for scams and bullshit (at least most of the time). I used to work in sales. I’ll just leave it at that.

“Disruption rocks though!”

No, it doesn’t. The right kind of disruption rocks. The kind that has value, that solves a problem, that improves an imperfect system. But disruption for the sake of disruption is just noise. It can even be destructive, and that doesn’t rock. It doesn’t rock at all.

Because Apple was “disruptive,” anything deemed disruptive now somehow borrows from Apple’s cachet. “Disruption” has become another meaningless buzzword appropriated by overzealous cheerleaders of the entrepreneurial clique they aspire to someday belong to. And look… every once in a while, someone does come up with a really cool and radical game-changing idea: Vaccines, the motorcar, radio, television, HBO, the internet, laptops, smart phones, Netflix, carbon fiber bicycles, drought-resistant corn, overpriced laptops that don’t burn your thighs in crowded coffee shops… Most of the time though, “disruption” isn’t that. It’s a mirage. It’s a case of The Emperor’s New Clothes, episode twenty-seven thousand, and the same army of early first-adopter fanboys that also claimed that Google Plus and Quora and Jelly were going to revolutionize everything have now jumped on the next desperate bandwagon. What will it be next week? Your guess is as good as mine.

I don’t know much about the hidden mechanisms of addiction, but I can’t help but notice a pattern with a certain crowd. There’s a compulsion there to jump on every new fad and build it up as something it clearly isn’t, right down to its unfortunate nomenclature. That’s probably why it isn’t unusual to hear fans of the “shared economy” talk about how this model is a new form of capitalism, how it’s going to change the world for the better. “Cab drivers refuse to evolve, man. They have only themselves to blame if they can’t compete. This is the future!”

Again, no. That’s not what’s happening. Could taxi companies stand to get better at using tech (like they do in Bogotá, Colombia)? Sure. But you aren’t talking about helping them do that, are you. You aren’t lauding a company that set out to bring cab companies into the 21st century. What you’re doing is lionizing the ticket-scalpers of the hired car industry just because they use a popular app. When you do that, you aren’t praying to the altar of progress or even tech Darwinism. You’re praying to the altar of “disruption.” It doesn’t matter how chaotic or damaging it may be as long as it’s disruptive. You’ve just jumped on the latest tech bandwagon without bothering to look at the big picture. Again. Which is to say that you’ve fallen for the latest hype bubble, the latest bit of messaging, the latest round of investment-driving marketing. You’re just parroting PR copy without questioning its validity in the real world.

And you know what else? (And this is actually more important.) That isn’t the future you’re looking at. It’s just an app-assisted reboot of the past. I’ll get to that in a sec. First though, this:

Piracy by any other name is still piracy.

If you really believe that a “ride-sharing” or room-booking service that deliberately attempts to avoid a country, state or city’s laws regarding licensing, insurance, fees and rate limits is somehow “competing” with legitimate taxis, hired cars and hotels, you’ve probably also rationalized that scoring your music and TV shows for free from pirating websites is somehow an example of legitimate market competition too. Well, it isn’t. Two sets of rules for “competitors” usually doesn’t end in fair competition – not in sports, and certainly not in business. Tip: There’s a reason Lance Armstrong was stripped of his 7 Tour de France victories, and it wasn’t because his training model was “disruptive” or “innovative.”

If, like me, you really want to see who comes out on top of a fair market competition between an Uber and an incumbent taxi company, then you have to level the playing field: “Ride sharing” services need to pay the same fees as the cabbies. They have to apply for the same licenses and permits. They have to submit to the same requirements in regards to driver qualifications, vehicle inspections, insurance coverage. They have to pay the same fees. If and when they start to do that, you’ll have a level playing field, and may the best business model win. Until that happens, good luck convincing authorities and the public that they aren’t running illegal taxi services and engaging in fare piracy.

Harsh words, I know, but that’s reality. Deal with it. And if you don’t believe me, go have a chat with a professional cab driver in NYC or Brussels or Paris or London. They’ve invested in their business. They’ve played by the rules and obeyed laws which are there to protect them AND consumers. Laws that took decades to come up with by the community in which they apply, whose intent was to established the most ideal balance possible between cab fares and consumer protections. Shattering all that work isn’t the kind of “disruption” anyone who understands the checks and balances of that market actually wants. What’s the impact on urban planning? What’s the impact on traffic congestion? What’s the impact on people’s quality of life? All of these things matter, and more so now than a generation ago. Per Frank Pasquale (University of Maryland School of Law) and Siva Vaidhyanathan (University of Virginia):

As allegedly “innovative” firms increasingly influence our economy and culture, they must be held accountable for the power they exercise. Otherwise, corporate nullification will further entrench a two-tier system of justice, where individuals and small firms abide by one set of laws, and mega-firms create their own regime of privilege for themselves and power over others.

While you’re at it, read their piece in The Guardian. It’s pretty great.

Footnote (from the same piece):

“Nullification” is a wilful flouting of regulation, based on some nebulous idea of a higher good only scofflaws can deliver. It can be an invitation to escalate a conflict, of course, as Arkansas governor Orville Faubus did in 1957 when he refused to desegregate public schools and president Eisenhower sent federal troops to enforce the law. But when companies such as Uber, Airbnb, and Google engage in a nullification effort, it’s a libertarian-inspired attempt to establish their services as popular well before regulators can get around to confronting them. Then, when officials push back, they can appeal to their consumer-following to push regulators to surrender.

Again, could cab companies stand to upgrade their tech? Absolutely. Does it mean that anyone with a car should be able to steal their fares by running a part-time, unbonded taxi service from behind the wheel of their Camry? No. And if you want to bring up the old line that “the old taxi model is corrupt,” don’t. If the new system aimed to end that corruption, you’d have a point. But it doesn’t. There’s no high road here. Replacing anecdotal incidences of corruption with a nullification scheme isn’t improvement. It’s the opposite. Bring ethics up again if and when ride sharing services ever manage to occupy that particular high road.

Before you brand me a hater or an enemy of startups, understand that I am the exact opposite: I love startups. I love new ideas. I want to see more of them. Any way we can improve on a model is something I can get behind. Cheating though, covering up unethical practices with crackerjack dogma, that’s something entirely different. And success obtained via illegitimate means isn’t success at all. You think that “breaking the rules” makes you a rebel or a rock star? No. It makes you a cheater.

Tip: If you really want to be a rebel, make your idea so great that people will want to rewrite the rules. That’s the difference between a change agent and a cheater, and it’s time we started making that distinction.

I won’t say much more about the devastating economic impact that unlicensed cabs can exert on taxi drivers, and unlicensed hotels can exert on small independent hotel operators (it isn’t all about Hiltons and Marriotts). That isn’t the topic I really want to dig into today. We’ll circle back to the very real (and dangerous) socioeconomic consequences of shattering full-time gig models in favor of opportunistic part-time gig models, but for now, I want to bring this back to the term “Sharing Economy” real quick, and why it is such a misnomer.

For starters, renting isn’t the same as sharing.

Let me make something really clear: that whole “ride-sharing” thing? It isn’t ride-sharing at all. You aren’t sharing. You’re renting. You’re renting out the back seat of your car. You’re renting yourself as a driver. You’re renting your spare bedroom for the night. You’re renting your flat while you’re on vacation. There’s no sharing anywhere near the so-called “sharing economy.”

If you really want to see the sharing economy in action, check out timeshares. Check out farming co-ops. Check out hippie communes. Hell, join your local homeowner’s association (or rather… don’t). Even profit-sharing at your company is part of the sharing economy. There are tons of examples of legitimate “sharing” economic models out there if you actually look. Here’s how an actual “sharing economy” works: a group of people co-owns and shares property or certain resources, and they get to enjoy their use based on their ownership shares. Neighbors operating small farms might purchase a harvester together, for instance, and share both its maintenance costs and its use throughout the year. With a timeshare, a group of owners owns shares in a piece of property and they share both its use and its costs. That’s how sharing works.

Other examples of shared services we run into every day: 911/emergency responders, public transportation, public schools, public parks, and so on. That fire truck screaming down your street to go put out a fire a couple of blocks away, you’re sharing that with the rest of the community. You all pay for it. Your resources are pooled together to provide this service for everyone. Because government is the operator in these instances, this is a more socialist model than the entirely capitalist timeshare, but the principle is the same: sharing is sharing. Anything that isn’t sharing isn’t… well, sharing.

So if one of those farmers we mentioned earlier decides to rent the co-op’s tractor through some tractor-sharing app (let’s call it Tractr), or decided to turn his farm into a boarding house for itinerant drifters heading West in search of actual jobs (good luck with that), that would be renting, not sharing. The moment you start renting something, you move into the “Rental Economy.” It’s just… there’s nothing new or sexy about that, so what would be the point of even talking about it?

(Exactly.)

You think this is revolutionary? No. It’s just another sales pitch.

What about the Collaborative Economy?

My friend and colleague Jeremiah Owyang has dubbed this movement the “Collaborative Economy,” and I applaud the effort, but… I have to respectfully disagree with the use of that terminology when it encompasses rental models. There’s nothing more “collaborative” about charging someone to sleep on your couch than there is about charging someone to book a room at one of your hotel properties. No one is actually collaborating. Buyers and sellers are just using an app to transact. That’s all. The only thing that’s new here is that the marketplace has shifted from the web to an app.

(Airbnb and Uber might as well be offshoots of eBay when you really think about it.)

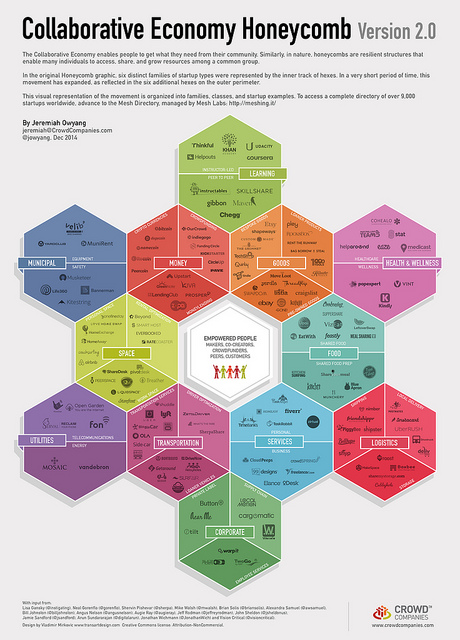

A true “collaborative economy” would be more applicable to crowdfunding services, for instance, or apps that connect individuals and organizations to one another based on their ability and willingness to actually collaborate on projects: “I’m looking for engineers to help me design a $5 water purification system for disaster zones” is a collaborative ask. That’s a legitimate “collaborative” model. And to be fair to Jeremiah, he does include these types of companies in his giant chart-o’ collaboration. That chart though… may be a little too inclusive. Case in point: “I need a car to pick me up at my hotel and take me to a club” is about as collaborative as “my yard looks like crap and I really need to find a cheap landscaper.” You’re talking about buying and selling services now, not collaboration.

Let me ask you this: if someone pushed out an escort-booking app (let’s call it Hookr), would that be “collaborative” too, or is it only collaborative when the transactions involve cars and apartments?

Context matters: Co-creation apps are collaborative. Co-curation is collaborative. Helping make higher education available for free on the web is collaborative. Wikipedia is collaborative. Crowdfunding and P2P loans are collaborative. But renting myself out as a part-time driver or a weekend boarding house manager without a business license or proper insurance isn’t collaborative. We can pretend that the collaborative economy “an economic model where technologies enable people to get what they need from each other—rather than from centralized institutions,” and that certainly can be the case, but most of what we’re actually talking about is a mobile marketplace for rentals and sales.

And that’s the crux of my objection: If collaborative economy discussions were about true collaboration apps, we would have something to talk about. But they aren’t. What leads those discussions? Uber, Lyft and Airbnb. When we hear about how big their footprint is, those numbers include Uber, Lyft and Airbnb. When we talk about the financial aspects of the market’s size, who comes up again? Uber, Lyft and Airbnb. Incorporating renting apps into the model skews the numbers. It skews the terminology. It’s a lot like trying to classify pizza as a vegetable: you can if you want. If you’re willing to twist yourself into a pretzel to make the logic work, more power to you. But you know it’s ridiculous.

Note: You should definitely check out Jeremiah’s work on this. (We only really disagree on two points.) Regardless of where you stand on the issue, his work is important and relevant. He is probably the best resource on this topic today, and his charts and graphics will help you become well-versed in this complex ecosystem.

One of the most helpful bits of content you are likely to find is his handy honeycomb graphic:

The Gig Economy:

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recently used the term “gig economy” to describe this movement, and that’s actually not bad. It’s catchy. More to the point, it fits a certain piece of this: The piece that focuses on part-time employment (assuming we can call it “employment” at all). The piece that lets creatives hire themselves out by the hour or by the task, for instance. Fiverr and Task Rabbit fit into the gig economy, obviously. Even Craigslist fits in there somewhere. Nothing super sexy or high tech about that. And I think that’s the part that bothers me the most about the massive hard-on some people seem to have for the so-called “sharing economy.” In spite of all the noise, and even aside from the flagrant semantic misdirection, there’s nothing really all that new or original about any of it. The only thing that’s new is that it works via apps instead of yellow pages, flyers and ads. The tech is new(ish) but the model is essentially the same as it’s always been.

Worse yet, the model itself caters to the worst aspects of neo-libertarianism (no rules, no regulations, no oversight, no workplace protections, no safety nets, and so on). It’s as cynical and even a little desperate. It can even be predatory and opportunistic… which would be somewhat fine if the prize were worth the cost to the community, but the reward is basically worth pennies on the dollar, which makes it a zero-sum game for everyone not standing to make real money on the back end. It undermines full-time employment. It undermines workplace protections. It undermines income security. Follow that daisy chain long enough and you’ll see how it impacts consumer confidence and spending too. And does it at least lower the cost of goods or increase real GDP? Nope. It doesn’t.

Here’s the truth of this model: look at it long enough and you’ll start to see how Dickensian it really is. And once you see it, once you get what it really is and where it really leads, you can’t unsee it. For more on that, read this bit by Alexander Howard (Huffpo’s Senior Tech and Society Editor).

Here’s an exercise: Imagine a world where nobody has full time jobs anymore, where everyone is a contractor. For some of you, that will probably seem like some kind of entrepreneurial utopia, a libertarian dream. In theory, sure. It sounds kind of cool because “freedom”… but then you realize that it’s the kind of model that we did away with in the early parts of the 20th century, and for good reasons: A “gig economy” cannot produce or support a healthy middle class. It doesn’t factor-in realistic retirement planning or college savings. Because it eliminates income security, it all but eradicates upward mobility. What you end up with is a 1% class (more like a 5%) and a 99% (95%) class, which isn’t super healthy for any economy, as history shows us time and time again. Fully realized, that gig economy looks like this for the 99%: selling and renting everything they possibly can to make ends meet and save a little money here and there. For the 1%, it cuts most of the cost out of running a business, which is kind of the point.

Don’t worry, I’m not here to make a slippery slope argument. The world isn’t going to slide into a dystopian future where the starving homeless masses fight each other in bloody rickshaw wars over trivial absurdities like Yelp reviews. I’m only trying to make a point, and it’s this: we’ve been here before, and it wasn’t pretty. We don’t need or want to go back to that model. The “gig economy” isn’t something new or cool or ultimately beneficial to anyone except the handful of clever CEOs and their investors, who have managed to convince masses of “independent contractors” (not really) to go out and break up the very fabric of local economies so they can make a few bucks and feel like they’re part of some kind of biztech revolution. It’s a mirage. It’s a con. Speaking of which…

Here’s a tip: No matter what apps you use on your phone, you aren’t Steve Jobs. You aren’t Richard Branson. You aren’t a maverick. You aren’t part of something grand. You’re just moonlighting as an amateur cab driver or a handyman so you can maybe pay off your student debt before you’re 80 (or just buy a bigger flat screen TV for your ridiculously overpriced mousetrap of an apartment). So before you start telling me how awesome this “sharing economy” revolution is, and how important you are to it, take a step back and get some perspective.

That’s why terms like “the sharing economy” are so dangerous: they sound so benign, so positive… They make you think that you’re doing something good for yourself and the world, that you’re part of some great wheel of progress. You’re sharing after all, right? You’re collaborating? Well, no. What you’re really doing helping tech dudebros with no concept of the real damage they are about to cause undermine local economies (and your careers) just so they can take their companies public and buy their third yacht. That isn’t an indictment of capitalism, by the way. (I happen to like capitalism. And yachts.) It’s an indictment of tech con jobs (i.e. bubbles) and irresponsible economic behaviors. And what do you get out of it? A little extra cash on the side? Awesome. How about a side of higher taxes to go with that, when all the cabbies and small business owners in your town have closed up shop? How about a dessert platter of more crime, dirtier streets, and an uptick in substance abuse and suicide when all the full time jobs have been replaced by low-bidder independent contractor apps? You haven’t really lived until your municipality’s tax base tanks to the point where there isn’t enough money to pay teachers, cops and street sweepers, and your property loses half of its value inside of ten years. How about a little shot of ice cold no-retirement-for-you to wash it all down with? Bravo. Way to see the big picture. And guess what: the guys who built those apps, who sold you on the “sharing economy,” they aren’t living in your neighborhood, are they. They don’t have to “share” your experience or your shattered local economy. They’re hundreds of miles away, on the other side of an ivy-covered gate or a gorgeous marina, wondering how to squeeze more money out of you with their next prepaid startup du jour.

And look… I don’t want to make this about class warfare. I really don’t. I’m not going to be that guy. That’s why I don’t want to give too much credence to cynical terms like “the Serf Economy.” But it isn’t hard to see why they’re beginning to catch on. We’re all lining up to become drivers, maids, delivery boys, babysitters, lodgers of fortune… and for what?

More importantly, for whom?

As much as I dig the cool choices Airbnb gives me whenever I travel, the big picture doesn’t seem all that awesome to me. Something’s broken here, and it doesn’t take a genius to see it. So before we get too deep into this “revolution,” maybe it wouldn’t suck to give some thought to what it really is and where it is taking us. (That extra $50 in your pocket comes at a price.) Case in point, via Tech Crunch’s Jon Evans:

Let’s face it, “sharing economy” is mostly spin. It mostly consists of people who have excess disposable income hiring those who do not; it’s pretty rare to vacillate across that divide. Far more accurate to call it the “servant economy.”

So what’s the fix?

The fix is simple: Level playing fields. Fair markets with controls. That means regulation, oversight, rules. I know that doesn’t sit well with the “deregulate all the things” nullification crowd, but there’s a reason we have those kinds of protections. They protect small, privately owned companies from being smashed to bits by giant global conglomerates and fraudsters. They protect full-time workers from losing their jobs to cheap and/or disposable part-time labor. They protect water quality and air quality and food safety. Everything from speed limits in school zones to building permits is there to protect someone from getting hurt. Sometimes, those rules protect our physical safety, and sometimes they protect our combined economic safety. If better controls over bank practices had existed pre-2008, we wouldn’t be in a recession right now. If better controls over pollution and greenhouse gas emissions had existed for the last 50 years, we might not be dealing with drastic climate change right now either. Rules might seem sucky and unfair when you’re six years old, but for the most part, they’re what ultimately holds our civilization together. They’re the mortar. Let’s not forget that.

And if your argument against this hovers along the lines of “the world isn’t fair,” or “survival of the fittest,” or some other law-of-the-jungle-inspired bit of “toughen-up, buttercup” BS, (you know who you are), this is the part of this post in which I probably need to remind you that you aren’t actually living in a jungle. You’re living in civilized society, protected within its walls, which are paid for mostly by everyone you’re trying to dismiss as useless or disposable. Like it or not, you’re part of that community. And I get it: being a predator is super cool if you’re in the wild. I totally understand if your power animal is the cunning wolf or the mighty lion. But… look at you. You’re no wolf. You’re no lion either. On a good day, you’re barely a muskrat. You wouldn’t last the night in an actual jungle. So now might be a good time to stop being a delusional wrecking-ball of a sociopath, maybe, and start treating the community you live in like the fragile ecosystem it actually is. Be a leader: improve the system instead of wrecking it for your own benefit.

Okay. Back to terminology.

The Microtransaction Economy:

I’ll tell you what this really is, what it should really be called: the Microtransaction Economy.

I know. It isn’t sexy. You aren’t going to sell that to millions of people as something cool or exciting, but that’s all it is: microtransactions. A fare here, a fare there, $5 for a logo, $7 to deliver a pizza, $10 to wash someone’s car, $15 to babysit someone’s pug while they’re at the nail salon, $30 to let a stranger crash on your couch for the night, $50 to drive someone to the airport, and so on.

You aren’t sharing. You’re selling and renting little blocks of your life for a few bucks and giving your opt-in marketplace a cut of the action. No matter how well it adds up at the end of the month, it’s a means to parcel out your time and your resources so you can rent them in convenient little blocks. No business license required. Minimal fees. No permits. No inspections. Just you and some single-serving customers looking to do a quick bit of business through your phones. Like it or not, it’s no different from selling oranges out of the trunk of your car on the side of the freeway, or selling concert tickets in the parking lot. Just because you use an app to do it doesn’t make it any more modern or disruptive. It is what it is: a super efficient market that fits in your pocket.

It isn’t all that different from this adjacent microtransaction model, by the way, which gamers should be pretty familiar with by now. In this instance, you may not be transacting with a “peer,” but the principle is the same: you’ve opted into a convenient virtual marketplace that happens to live on your device. Whether the seller is a $10B company or some guy who lives three blocks away, what difference does it really make? A market is a market.

And don’t get me wrong: I don’t begrudge anyone the decision to make more money however they can, especially in this economy. You have to do what you have to do. But once you realize the extent to which these everyone-for-himself models end up undermining the very mechanisms that we should collectively be fighting to preserve and strengthen, it’s hard not to feel a little discouraged and cynical about how easily people can be manipulated into working against their own interests. It’s proof that the right kind of sales pitch and packaging can turn us into our own worst enemies, and I think that’s both scary and sad. In the end, the only we may end up actually sharing in this so-called “sharing economy” is the big ugly bag of consequences that we’re all collaborating to bring down on ourselves. Give that some thought.

Okay, that’s it. I’m done. Feel free to agree or disagree. The comment section is all yours. As always, try to keep things polite, but if you can’t, that’s okay.

Cheers,

Olivier