The slow wheels of reform and harmful mutual obligation

In this week’s blogs moderator @simonecasey draws attention to ongoing concerns about harmful mutual obligation policy under the Targeted Compliance Framework that needs to change sooner not later.

Senator Janet Rice’s Estimates swansong delivered revealing cross-portfolio questions at the February hearings. At these Estimates the Senator honed in on issues relevant to mutual obligations and employment services, and how these intersect with the problems people have been having with Services Australia more broadly.

In the Community Affairs hearing, the Senator pursued answers on wait times for income support and pension claims processing and telephony congestion. Of course, the 3000 new staff Services Australia have been training will help to fix these issues but there are real problems now that mean people can’t get through to find out when they’re going to get a payment, and/or sort out any issues they have with payment penalties. In the case of the latter, this means that the 1,700 people in the Targeted Compliance Penalty Zone may not be able to get through to a human decision maker about payment penalties they have received.

Secondly, in the Employment Estimates, the Senator pursued answers on payment suspension and demerit point strike rates for First Nations people particularly in regard to suspension rates for providers who have specialist operating licences to work with both ex-offenders and First Nations people.

The Department of Employment explained that the higher strike rate for those providers reflected the higher concentration of those on their caseloads and this is the reason they are statistically over-represented. But surely the point of operating specialist licences is to provide sensitivity to the social and cultural needs of those people - not to use the blunt force of mutual obligation compliance tools steeped in the penal legacy of colonisation.

As well as these high strike rates for individual providers, it was also revealed that payment suspensions affect Indigenous participants at a higher rate than non-Indigenous across the board, that is 62.7 per cent versus 40 per cent. This clearly shows that the compliance framework is, as it always has done, is perpetuating harms to First Nations people at higher rate than others.

The unconscionable rate of payment suspensions has continued to receive media attention, and what is becoming increasingly obvious is that they are based on poor administration of social security law by employment services providers due to the impossible rules they are required to administer.

The poor administration has a number of elements. The first is that it is practised by a person rather than a computer, as the majority of suspensions arise because of the actions of a human decision maker. But these workers act within tight constraints of ‘guidelines’ about the process they must follow.

One such as example is the process they follow when someone has not attended an appointment. Administrative law requires a person to have been able to provide a reason before a payment suspension. This is reflected in the process that providers are supposed to follow to call a person on the day of the appointment. If they don’t make contact by the end of the day the worker enters a code on the IT system to say the person did not provide a reasonable excuse. There is very little room for discretion not to enter this code as the guidelines prescribe this. This is what the guidelines say:

When the Provider attempts to contact the Participant in accordance with the above obligation and the attempt is not successful, the Provider must record they are not in contact with the Participant and select ‘Did Not Attend—Invalid’ (DNAI) in relation to the relevant Mutual Obligation Requirement in the Participant’s Electronic Calendar.

Following this if a person does not make contact within 2 days the payment is suspended due to the code (DNAI) entered by the worker. The two-day grace period acts as a notice of impending suspension, which for all intents and purposes for the person affected becomes the start period of a suspension - as the notification of imminent suspension causes people to experience stress in the same way as a suspension itself.

Many moons ago it was noted that providers are not experts in social security law, but they are required to be experts in the administration of the employment services contract and the associated guidelines. Staff are trained in myriad learning modules and must be conversant with the associated 1000 guidelines and related documents, fact sheets, task cards to keep abreast of updates and changes in the rules. The reality is there is far too much of a requirement for the providers to be compliant with the documents, rather than operate autonomously and to use discretion about a person’s circumstances. This is reflected in the fact that they use a drop list of categories for social security decisions about a reasonable excuse (called a Valid Reason) rather than applying their own discretion.

It is difficult to ensure the quality of the services when staff turnover is so high, and this means that their ‘expertise’ is constantly compromised . So workers make decisions within unreasonable timeframes, under workload duress and without flexibility to practice administrative discretion.

To add to the complexity there are a range of reasons that people are uncontactable when providers put in their calls to find out reasons for non-attendance. Nevertheless the minimal effort to make contact is taken as sufficient to satisfy the administrative law requirement for an opportunity for a reasonable excuse to have been provided before the payment was suspended.

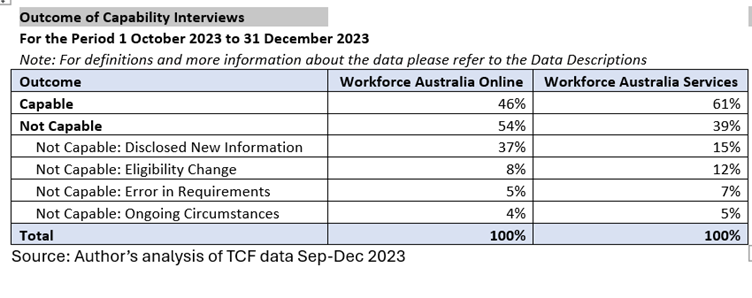

An example of how provider discretion varies to those of Departmental personnel is reflected in my analysis that compared outcomes of capability interviews for people in Online versus Provider services below. I noticed that Contact Centre staff (employed by DEWR) make decisions more favorably than providers. The table below shows that 15% more participants are found to be ‘capable’ of meeting requirements, than those whose situation has been assessed by the Digital Contact Centre. This means providers are sending people into the dreaded financial penalty zone more often than Departmental staff.

Considering that those people in provider services are already more highly disadvantaged it is not unreasonable to expect that they would have more difficulty meeting requirements. Since those people will continue into the compliance penalty zone, you can see how the compliance system perpetuates harms on people who are already the most disadvantaged.

We know that people in Workforce Australia provider services are highly disadvantaged and that providers are struggling to retain staff. When faced with this evidence there are good reasons why payment supensions should be paused because systemic reforms are still too far off.

The views in the article are my personal views based on my independent and academic research into employment services and mutual obligations.