Policy in Australia: 'throwing the spotlight of academic inquiry on murky and ambitious work'

The newly published Policy Analysis in Australia is Australia's contribution to the International Library of Policy Analysis series.

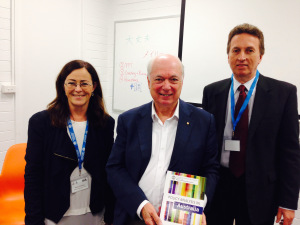

It is edited by by Brian Head, right, Professor of Policy Analysis at the University of Queensland and Kate Crowley, Associate Professor of Public Policy at the University of Tasmania, and recently launched by ANU public policy professor Andrew Podger. See his speech here, via The Mandarin, and the editors' blog post: Policy analysis in Australia: complexities, arenas, and challenges.

Below, taken from the book's Foreword, former Prime Minister and Cabinet department head Peter Shergold welcomes "the first systematic overview of policy analysis in Australia" and looks over his own experiences in policy-making: the challenges, achievements and (most interesting to his students, he admits) failures.

FOREWORD: Peter Shergold

Analysis of public policy has formed the core of my working life. I feel fortunate to have been involved in many of the key changes in policy development processes that have taken place over more than 40 years. I’ve watched, participated – even occasionally influenced – from vantage points in academia, public administration, corporate boardrooms and the not-for-profit sector. I’ve practised and preached. From that variety of perspectives I warmly welcome this well-edited book which, through its varied contributors, reflects thoughtfully on many of the important dimensions of policy change and innovation.

Migration issues

A generation ago, in 1987, I moved from academia to the public service. I was Head of the Department of Economic History at the University of New South Wales: I became Head of the Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C). I relocated the short distance from Sydney to Canberra, but I quickly began to understand that I had travelled between two different worlds. Over time, learning by doing, I came to look at public policy with different eyes. I found few books to guide me on my journey.

Even as an Associate Professor I had sought to influence government decisions, particularly on migration issues. In truth, my approach to political persuasion was pretty ineffectual. As an academic I wrote scholarly papers on the economic consequences of immigration to Australia and tested hypotheses on the influence of racial and ethnic discrimination on labour market outcomes. As a consultant I provided advice to governments through papers on settlement and multicultural issues that were commissioned by the Ethnic Affairs Commission of NSW, the Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs and the Commonwealth Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs. As a community advocate I worked on a voluntary basis for the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils, writing and lobbying – and even, on occasion, publicly protesting – in support of a more liberal migration regime.

In 1984, at the height of fierce public debate on Asian migration, I co-edited a volume on The Great Immigration Debate. It was quite successful, going through a number of editions and being recorded as an audio book. In the process I locked policy horns with a far more distinguished economic historian-turned-commentator, Geoffrey Blainey. None of my involvement had much impact on government policy although perhaps my participation in public debate helped me to be considered for the position at OMA. Then again, perhaps no career public servant wanted the job. No matter: I joined the Australian Public Service (APS) for three years which, in no time at all, became two decades. In that time I headed seven government agencies, including PM&C. It was, I felt, a career that had purpose. I loved it.

Triumph and failure

Since leaving the APS and returning to university life (albeit only as a Chancellor), I have reflected at length on the theory and practice of policy analysis. I think a great deal about how it may be possible to enhance the quality of government decision-making. Inevitably, my evolving views have been heavily influenced by my own experience. My musings have been those of a practitioner who, in a triumph of hope over experience, still believes in the power of empirical investigation to create evidence-based policy - in spite of the fact that not infrequently in the past I have found myself contributing to policy-based evidence. I continue to view a mandarin’s covert exercise of influence largely from a utilitarian and instrumentalist rather than a theoretical perspective. Moreover I perceive the skill requirements are more in the nature of administrative craft and managerial mystery than political science.

Regrets, I have a few. I count myself fortunate to have led OMA in drafting the National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia in 1989; contributing to framing public policy around the legislative response to the Mabo High Court decision on native title in 1992; to setting the intellectual groundwork for a values-based, non-prescriptive Public Service Act in 1996; to establishing and managing the Jobs Network in 1997; to widening the range of higher education options available to students in 2002; and to formulating the development of a comprehensive Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Reconstruction and Development in response to the tragedy of the Asian tsunami in 2004.

Triumphs of policy, of course, often turn to dry dust in one’s hands. Against the political odds, and after some years of quiet endeavour, I was able to garner sufficient support to persuade Prime Minister John Howard in his final months in office in 2007 to accept the virtue of a market-based emissions trading scheme. It was, I argued, the best way to address the risks of anthropogenic climate change in the most cost-effective manner. Yet the recommendations of the Task Group on Emissions Trading (the so-called Shergold Report) were effectively rejected by the incoming Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, perhaps because they were seen as representing too conservative and cautious an approach to what was briefly the world’s greatest moral challenge. After years of political machinations there is still no ETS in Australia. The Report now survives somewhere deep in the National Archives as an archaic piece of policy analysis, forgotten except by aficionados of political trivial pursuit. Unlike Roman heroes, those engaged in public policy do not need to have a slave whispering in their ear to remind them that they are mortal. Memento mori could be the appropriate motto for departmental secretaries.

The sorry fact is that every little triumph I enjoyed was matched by a commensurate and counter-balancing failure. In spite of my growing ability to frame issues, set agendas, present evidence, give frank and fearless advice, identify alternative options and foresee unintended consequences, the policies I administered were often very different from the ones that had initially been put forward to Ministers. Conceptual and analytical skills, the intellectual capacities extolled by public service executives, were often not enough. Not a few of my policy suggestions, set out carefully in briefs, never saw the light of day. The fact is that the corridors of power often come to dead ends: alternative routes turn out to be blind alleys. Public policy is hotly contested from many different perspectives, often leading to risk-averse procrastination or deadlock. Politicians only have so much political capital they can waste on what they perceive to be bureaucratic flights of fancy. Public servants, after all, do not have to worry about being re-elected. Just because a policy is elegant does not mean that it is persuasive.

Policy shortcomings

I left the APS more than seven years ago. Today I am quite often invited to speak on my experience at public service forums. I like to imagine myself as an enlightened older statesman but I have to admit that the most popular talk I present to students of the Australian New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG), which goes down particularly well as an accompaniment to postprandial drinks, emphasises my failures. The adversities that I’ve suffered in developing and delivering public policy are far more interesting than my successes, generally more humorous and nearly always more educative.

Policy shortcomings, I’ve discovered, can be attributed to a multitude of causes. These include the inability to mount a persuasive argument for change; a lack of substantive evidence, either of the dimensions of a problem or the means to address it; the tendency for reform initiatives to travel along the well-worn track of past endeavours, rather than heading in a more innovative direction; a reluctance to put in the relentless hard grind necessary to win broad stakeholder support; the inability to countenance frame and negotiate compromise positions; and – too often forgotten after the press release has been issued – the failure to execute policy to time, cost and public expectations. Good policy is not just a result of sound analysis. It is equally dependent on managing effectively the risks of implementation. Policy development and program delivery are two sides of the same coin.

Of course, there is a danger in going public about one’s weaknesses in policy analysis. When I reflected – in the Foreword to another book – on the manifold failures to which I had contributed in Indigenous affairs, The Australian gave my mea culpa headline attention and the distinguished Aboriginal leader, Noel Pearson, only half-jokingly suggested that I should be called to explain my epiphany before a Truth and Justice Commission.

I remain convinced that learning from one’s mistakes is a key ingredient of leadership. Perhaps, though, if I’d have read this book I’d have committed fewer errors. Certainly I wish that this insightful collection of essays had been available to me when I entered the APS. Together the array of authoritative contributors provide the first systematic overview of policy analysis in Australia. The book, too, is all the better for bringing comparative experience to bear on the arguments presented. As Secretary of PM&C it was enjoyable, occasionally, to meet with my counterparts from Canada, the UK and New Zealand and chew the fat on our experience of the varieties of Westminster. I doubt if we would have avoided all the errors that we imagined we had made but perhaps we would have better understood why we had committed them.

Fierce contests & complexity

Many of the chapters confirm the discoveries that I made, all-too-slowly, as I stumbled to master the vocation of public service. First and foremost, and as I came to proclaim repetitively at the annual inductions of graduate recruits to the APS, policy analysis is not a linear process. Verona Burgess, the perceptive public service journalist who continues to write in the Australian Financial Review, and who had the misfortune to attend far too many of these presentations, once mildly chastised me for always describing the whole wide world of public policy as being iterative in character. Yet my utterances, if predictable, were also true. Public policy analysis is fiercely contested – behind closed doors, in Parliament and in the public arena. Often there has been strident debate about the goals and objectives of policy, even when the arguments have been hidden from view. It is not just the answers to problems that are fought over: on occasion there is even a greater divergence of views on how to articulate the correct questions. Politics is a world in which opportunities have to be seized, differences resolved, compromises negotiated, financial implications reduced… and, not surprisingly, delays suffered.

This book bears testimony to the variety of state actors who now contribute to public policy. There are good chapters, both from academics and practitioners, on the important role of senior public servants working in all three tiers of Australian government. Yet no matter how persuasive the analytical judgement of a professional administrator, ministerial advisers – attuned to the short-term political realities that confront their political masters – will often view the world from a quite different perspective. Sometimes they will demand faster action, but at other times counsel caution; on many occasions they will vigorously argue out the issues, but on other matters they will skilfully (but inappropriately) exercise their role as gate-keepers to try and protect Ministers from seeing advice or considering approaches with which they disagree; occasionally they will be held publicly accountable but often their actions are hidden by the cloak of ministerial responsibility.

Public policy, however, is far more than a battle between apolitical public servants and political advisers for the attention of their Minister. Sources of influence have widened and, consequently, so has the complexity of decision-making. The role of a cacophonous medley of noisy advocates are also assessed in this book: Parliamentary Committees and Public Inquiries, Expert Advisory Councils, consultancy companies, think-tanks, business associations and industry and union lobbyists. In addition, not-for-profit, non-government organisations give voice to the cultural, environmental, social and economic interests of civil society. As the ‘third sector’ is increasingly paid to deliver outsourced government services so its potential ability to influence rises, although too often it finds its autonomy constrained by contractual restrictions.

At the same time, slowly but by no means surely, citizens themselves are also gaining a more significant role in policy formation, both through the largely untapped potential of digital democracy and as a result of the roll-out of consumer-directed care programs. Individuals – those with a disability, health patients and aged care recipients – are being given varying degrees of freedom to design and manage their own service provision.

Public policy, then, is a complex intermediation between a widening heterogeneity of state actors with different perspectives. Evidence – as knowledge – is brokered and negotiated, framed and re-framed. The role of public service mandarins, from my perspective, should not be to seek to outmanoeuvre the ‘boy scouts in the Ministers’ offices’ or the industry ‘rent seekers’ who they often perceive to stand as an impediment to good public policy: rather it is to facilitate an evidence-based outcome that respects the divergent self-interest of conflicting and sometimes countervailing viewpoints. A cross-jurisdictional ‘whole-of-government’ perspective is often elusive: so, too, are ‘win-win’ outcomes across sectors. The skill of a senior public servant should be founded on an understanding that public policy is appropriately a result of the application of political power to ‘evidence’, in a manner which can give rise to a variety of alternative outcomes. Facts may be objective but policy analysis is not.

This does not mean that there is limited value in taking a systematised approach to our understanding of the nature of policy analysis. Indeed, such a structured perspective on the role that diverse institutions play in analysing and influencing policy is highly beneficial. I am pleased that the task views such complexity in a positive fashion. Monopoly is rarely a good thing and in the manufacture of public policy it is unequivocally bad. No longer can initiatives be assumed to be best when they emerge solely from a confidential discussion between Ministers and the public sector agencies that they administer. Ideas need to be contested and policies debated. The key is to understand how outcomes are achieved and, through that realisation, to devise more effective ways to design and deliver good policy.

By throwing the spotlight of academic enquiry on the murky and ambiguous nature of policy formation, and by identifying the disparate perspectives of an assortment of players, this book serves an important purpose. Collectively, the authors provide both a positive and normative assessment of the nature of policy analysis. The editors understand that multiple sources of informed advice are healthy in a participatory democracy, whether they find their origins in political ideology or technical expertise. Diversity, for all its challenges, is recognised as a good thing.

Policy Analysis in Australia, then, is an important book. I enjoyed reading it. I found it helpful in expanding my lines of enquiry and challenging my assumptions. I learned from it. I feel confident that other readers will benefit in similar ways.

***

Policy Analysis in Australia is available to order here.