Are politicians doing what's needed to grow our cities?

The transport and planning policies routinely touted by politicians won’t equip Australian cities to cope with projected growth. In this post, Dr Alan Davies (@MelbUrbanist) argues that much more fundamental, but politically difficult, actions are needed.

This article was first posted on Crikey's Urbanist blog on April 1, 2015.

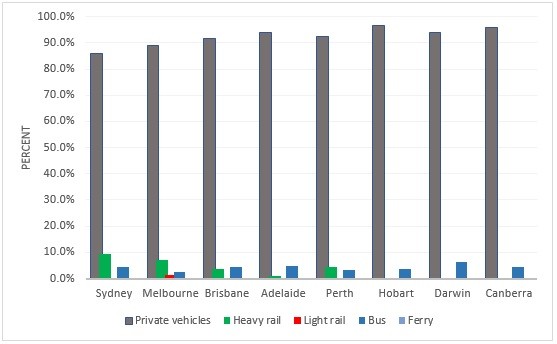

% share of motorised travel (kms) by mode, Australian capital cities, 2013 (source data: BITRE)

Premiers and Ministers around the country should have a good look at the exhibit above. They should reflect on whether the sorts of transport and planning policies they’re promoting are really likely to improve the longer term prospects of Australian cities in the face of strong existing and projected population growth (e.g. see here and here).

The exhibit shows the share of kilometres travelled by motorised modes in Australia’s eight capital cities in 2013. It’s based on updated data in a recent publication by the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE), Urban public transport: updated trends. (1)

Despite all the hype by governments over the last 15-20 years around measures like urban growth boundaries, urban consolidation and investment in new rail lines and motorways, it’s painfully evident that private vehicles are still the dominant mode, accounting for 89.6% of all motorised travel in the nation’s eight capital cities in 2013.

Private vehicles fare worst in Sydney but still generate 86.0% of passenger kms. Their highest shares are in Canberra and Hobart where they account for 95.8% and 96.5% respectively of all motorised passenger travel.

It’s clear that public transport hasn’t gained much ground on private vehicles in the nation’s capitals. BITRE reports the strong growth in public transport patronage over the period from 2005-2009 (4.7% p.a. across all capitals) hasn’t been maintained. It fell to 1.3% p.a. between 2009-2013, just keeping pace with population growth.

Light rail attracts a lot of interest as a mode of the future but its share of total motorised passenger travel is miniscule. For example, Sydney’s 6 km CBD to Lilyfield line accounts for 0.03% of the city’s total travel; even Melbourne’s trams only account for 1.3% of total metropolitan kilometres. (2)

I think the key message to take from the exhibit is that the standard solutions currently pushed by politicians are unlikely to be enough to accommodate the level of population growth projected for Australia’s cities. It’s delusionary to imagine we will somehow magically build enough new roads and rail lines to address issues like traffic congestion and pollution effectively.

Unfortunately, the cost of retrofitting transport infrastructure in urban areas in Australia is astronomical e.g. $11 billion to construct the 9 km Melbourne Metro rail tunnel.

The upgrade to Melbourne’s Cranbourne-Pakenham line announced by the Victorian government is expected to cost over $3 billion. It will increase capacity by 11,000 passengers in the morning peak in a city who’s citizens make in the order of 13 million motorised passenger trips on an average weekday.

Of course our cities will need better transport infrastructure but how much they can realistically build is problematic; it will have to compete with other demands for expenditure e.g. in education and health.

It can’t be assumed Sydney and Melbourne will get to a population of 8 million and somehow magically enjoy a similar level of public transport infrastructure as London or Paris. As it is, the extensive rail network inherited by Melbourne at the end of the nineteenth century was largely the result of unprofitable private sector ventures and corrupt political practices.

A much more fundamental commitment to action is needed than the sort of fluff that’s routinely put in strategic planning documents like Plan Melbourne. They might have a role over the first four or so years in setting out election promises, but beyond that they’re mostly marketing media.

Building infrastructure should be seen as just one of a number of steps that are necessary to prepare Australia’s major cities for future growth.

Federal and state governments need to also commit to structural changes like sweating existing assets much harder, suppressing and/or shifting the demand for travel at peak periods, aligning taxes and charges with the real social cost of activities like travel, and lowering the cost of building and operating transport infrastructure.

They also need to reduce regulatory constraints on higher density development, make housing markets more flexible, develop a much better understanding of likely future changes in transport demand and technology, and pick infrastructure projects with more regard for their social value than their political utility. (3)

The sorts of measures these actions imply – such as levying congestion charges on motorists – will of course be politically difficult. The trouble is there aren’t any easy solutions.

Dr Alan Davies is a principal of Melbourne-based economic and planning consultancy Pollard Davies Consultants. He blogs regularly on The Urbanist, part of Crikey's blog network.

Posted by John van Kooy

- Travel is measured by kilometres per passenger; this metric has a number of advantages over mode share estimates based on the number of trips. One is it accounts for differences in average trip lengths by mode (e.g. urban rail trip lengths are on average 2.3 times those of urban scheduled bus services). Another is it reflects more accurately the environmental impact of different modes.

- The extension of Sydney’s light rail from Lilyfield to Dulwich Hill wasn’t open in 2013. Similarly, the contribution made by ferries is so small it doesn’t show up on the exhibit; it’s just 0.2% in Sydney.

- Decentralisation and/or limiting population growth are often proposed as other options. They’re big issues that I can’t properly address here; for the purposes of this discussion I’ve assumed Australian cities will grow in line with projections.