Affordable housing policy failure still being fuelled by flawed analysis

Australia has a housing affordability problem. There’s no doubt about that. Unfortunately, one of the reasons the problem has become so entrenched is that the policy conversation appears increasingly confused. It’s time to debunk some policy clichés that keep re-emerging.

Is ‘zoning’ to blame?

It can be tempting to frame the housing affordability problem as all about inadequate new supply. According to this argument, the “demand side” drivers – such as low interest rates and tax incentives for property investment – have combined with population growth in the capital cities to fuel house prices, and new housing construction simply hasn’t kept up.

“Zoning” is often blamed. There is little hard evidence, though, to show systematic regulatory constraint.

Supply is at record highs, and in the right places

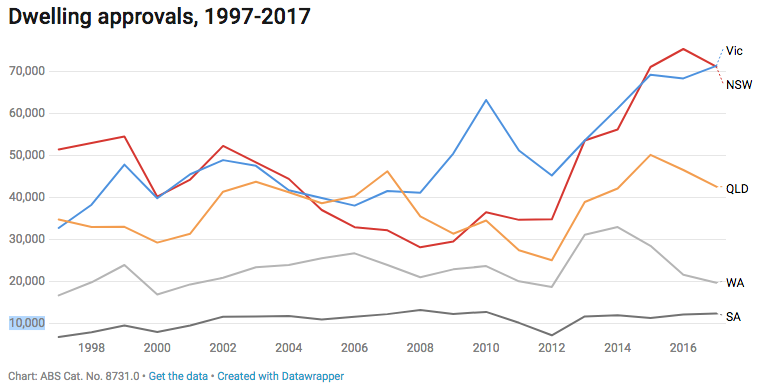

Australia’s new housing supply per capita is actually very strong by international standards. Over the past decade, supply of new units and apartments has been flowing in job-rich metropolitan areas with dense populations, which are also higher-value locations.

According to the cliché, this supply response should have cooled prices. Yet dwelling price inflation has surged even in metropolitan areas where new housing supply has exceeded population growth.

The fallacies of ‘filtering’

One of the great hopes underpinning the supply cliché is that new housing stock improves affordability even if these homes are not affordable for lower-income groups. This faith is based on a theory called “filtering” whereby older housing moves down to the affordable end of the market over time.

The empirical data on filtering are thin. Indeed, the academic literature has historically cast doubt on the theory. However, some commentators continue to claim that American rental housing markets provide evidence that “filtering” can occur in practice.

But whatever might happen in the US, in Australia there’s still no evidence to suggest new housing supply has filtered across the housing stock to expand affordable housing opportunities for low-income Australians, or that it will do so any time soon.

Prominent economists continue to produce data that suggest the potential impact of new supply on price is minimal. The shortage of affordable housing opportunities for low-income households in Australia remains persistent. And the evidence indicates that low-income working households in our cities consistently face housing costs well above accepted affordability levels regardless of the quality of the housing they live in.

Sustaining supply in a cooling market?

Some commentators cite cooling house prices as evidence that the supply response is taking effect. Whether or not that is so (above and beyond demand-side factors like higher interest rates for investor loans), expect the pipeline to start slowing down. Private sector development is driven by profit and risk and, as we have seen over many years, is characterised by speculative booms and busts.

Developers can turn off the new supply tap much more quickly than they can turn it on. Falling prices, weak consumer sentiment and economic uncertainty mean many developers will not follow through on building approvals until the market recovers.

This means that high levels of supply output are rarely sustained. Recent housing data in Western Australia provide a case in point. WA recorded rising completions in 2014, 2015 and 2016. But 2017 completion figures are expected to show a drop of around a third as prices have shaded off since the end of the mining boom.

Put simply, the market on its own will never solve Australia’s housing affordability problem. Expecting developers to keep building in order to reduce house prices is pure fantasy.

Planning reform is not an affordable housing strategy

We’ve written before about the political appeal of calling for planning reform instead of real solutions to housing affordability pressures. In fact, Australian states have embarked on more than a decade of planning reforms.

They have aimed to: standardise and simplify planning rules; promote mixed use and higher-density housing near train stations; and overcome local political opposition to development through the use of independent expert panels.

Housing targets for both urban infill and new greenfield areas have been a feature of metropolitan plans to drive dwelling approval rates since at least 2000.

These reforms have been effective in overcoming regulatory constraints. The scale of the recent supply response shows clearly that zoning and development assessment processes are not inhibiting residential development approvals in cities like Sydney and Melbourne.

But trying to accommodate Australia’s population growth in towers around railway stations will fail as an affordable housing strategy – even if “zoning” and height rules were completely scrapped.

Rather than narrow deregulation agendas, bigger picture reforms are needed. Aligning infrastructure funding with metropolitan and regional decentralisation is a critical long-term strategy. Reforms to deliver affordable housing in communities supported by new infrastructure are long overdue.

A bigger affordable housing sector is needed

Australia needs a more realistic assessment of the housing problem. We can clearly generate significant dwelling approvals and dwellings in the right economic circumstances. Yet there is little evidence this new supply improves affordability for lower-income households. Three years after the peak of the WA housing boom, these households are no better off in terms of affordability.

In part, this may reflect that fact that significant numbers of new homes appear not to house anyone at all. A recent CBA report estimated that 17% of dwellings built in the four years to 2016 remained unoccupied.

If we are serious about delivering greater affordability for lower-income Australians, then policy needs to deliver housing supply directly to such households. This will include more affordable supply in the private rental sector, ideally through investment driven by large institutions such as super funds. And for those who cannot afford to rent in this sector, investment in the community housing sector is needed.

In capital city markets, new housing built for sale to either home buyers or landlords is simply not going to deliver affordable housing options unless a portion is reserved for those on low or moderate incomes.

About the authors:

Nicole Gurran is Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Sydney; Bill Randolph is Director, City Futures Research Centre, Faculty of the Built Environment, UNSW; Peter Phibbs is Director, Henry Halloran Trust, University of Sydney; Rachel Ong is Professor of Economics, School of Economics and Finance, Curtin University; Steven Rowley is Director, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Curtin Research Centre, Curtin University

Posted by @jrostant