COVID-19 and mental health impacts: Women are at greater risk

The Australian government has recently announced a $20 million injection of funds into mental health and suicide prevention research, acknowledging that disruptions to usual routines due to COVID-19 are increasing risk. However, it is notable that where mental health research is funded specific to one gender, it is most often designated for males. Today’s analysis explains why lopsided funding is misplaced; women experience worse overall mental health compared to men, and they are also disproportionately negatively impacted by COVID-19 and its policy responses. This analysis has been adapted from a policy brief compiled by Women’s Health Victoria (@WHVictoria) for the Women’s Mental Health Alliance. Graphs appear courtesy of Gender Equity Victoria (@genderequityvic); view their infographics here. UPDATE: An updated (October 2020) policy brief is now available from Women’s Health Victoria.

Emerging evidence suggests that COVID-19 is having significant impacts on women’s mental health, and that this is compounding existing mental health inequalities between women and men.

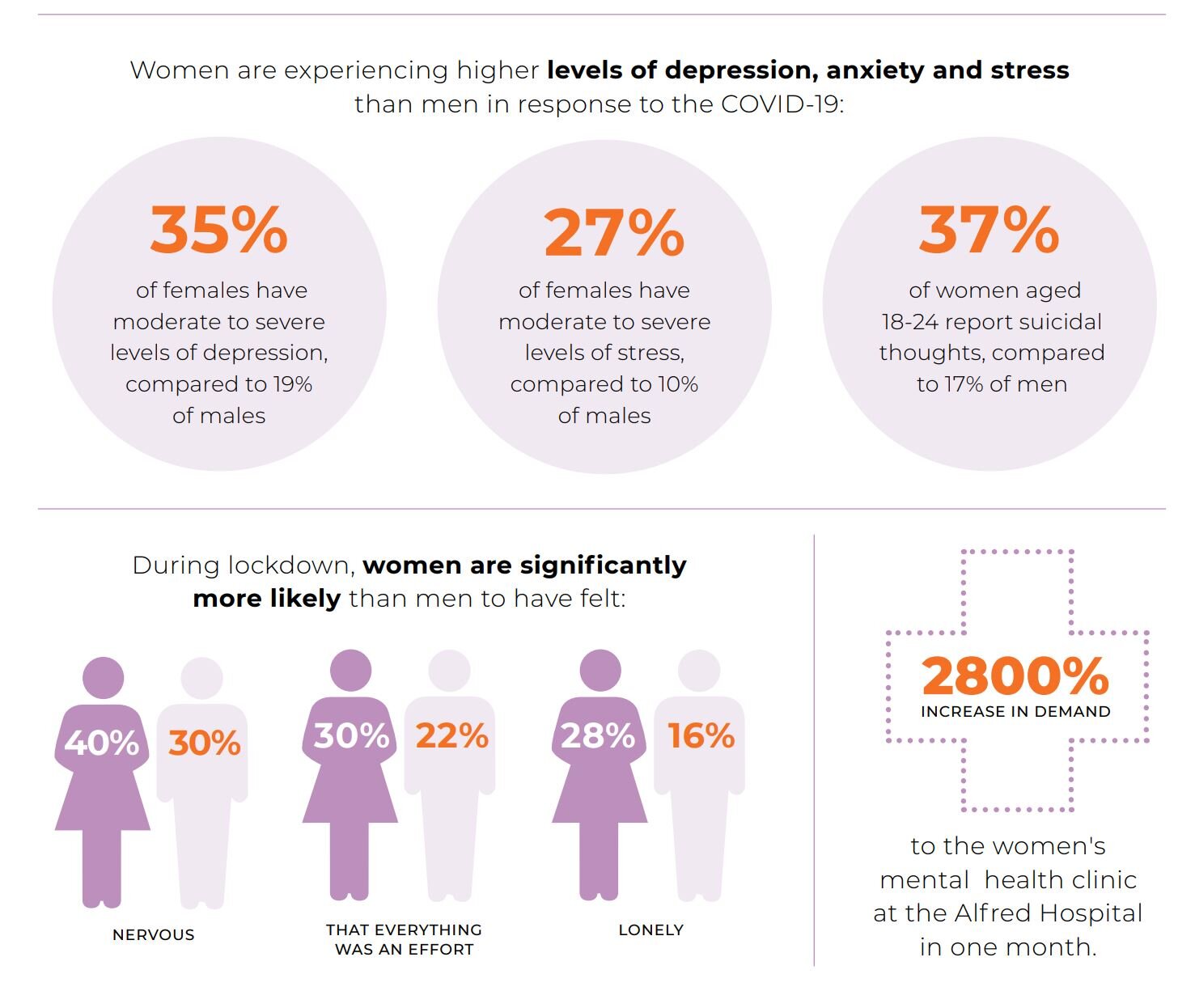

The ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey indicates that women are significantly more likely than men to have experienced negative mental health impacts. Women were more likely to feel: restless or fidgety (47% of women compared with 36% of men); nervous (40% compared with 30%); that everything was an effort (30% compared with 22%); and/or so depressed that nothing could cheer them up (10% compared with 5%). 28% of women have experienced loneliness, compared with 16% of men. These findings are consistent with data from the US and Canada showing that women are more likely to experience negative mental health impacts than men due to COVID-19. A study of 8,000 people in the US has found mental health has declined only among women during COVID-19, increasing the existing gender gap in mental health by 66%. Other survey data from Canada and the US suggests that women are more likely to report that worry or stress related to COVID-19 has had a major negative impact on their mental health.

The escalation in mental health issues among women is due, at least in part,[i] to intensification of pre-existing gendered social and economic inequalities:

The over-representation of women in casual and insecure employment means they are more likely to have lost their jobs.

Women already make up the majority of unpaid carers, and have taken on a greater share of additional care responsibilities for children, other family members and at-risk community members during self-isolation. The ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 survey shows that women are almost three times as likely as men to have been looking after children full-time on their own (46% compared with 17%) and are more likely to have provided unpaid care or assistance to a vulnerable person outside their household (16% compared with 10%).

The fall in the female labour force participation rate was almost 50% larger than the fall in the male participation rate in April, most likely reflecting the greater share of additional caring responsibilities that women have taken on.[ii]

Other forms of inequality and discrimination – in particular, racism, ageism and economic inequality – are compounding these mental health impacts for women. The frequency and severity of intimate partner violence also increases during and after emergencies, with confinement to the home creating additional risks.

Women have also been disproportionately on the COVID frontline: the majority of health care workers, social assistance workers, teachers and retail workers are women – exposing them to the dual stressors of high-pressure work environments and potential infection. As Professor Lyn Craig observes,

‘it is striking how many of the jobs that are now seen as essential involve care, and how many of them are female-dominated. Not coincidentally, they also pay well below the level the skills and qualifications would require if they were predominantly done by men.’

Women have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to poorer mental health. This does not appear to be recognised by government mental health policy. Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash

It has been observed that women are carrying a ‘triple load’ during the crisis, which includes paid work, care work, and the mental labour of worrying. All these factors lead to emotional, social and financial stress and anxiety, and can exacerbate existing mental health conditions, trigger new or recurring conditions, and impede recovery. At the same time, limited availability of gender-specific or gender-responsive services means women may not be able to access the support they need.

Women with existing mental health conditions

Those with current mental health concerns are especially at risk during emergencies and will likely experience barriers to accessing the appropriate medical and mental health care they need during the pandemic, resulting in decline, relapse or other adverse mental health outcomes.

Data from a survey conducted by Monash Alfred Psychiatry research centre indicates that women in Australia are experiencing higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress than men in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary analysis of data collected between 3 April and 3 May on 1495 adults (82% female) has found:[iii]

39% of females have moderate to severe levels of psychological distress compared to 31% of males

35% of females have moderate to severe levels of depression, compared to 19% of males

27% of females have moderate to severe levels of stress, compared to 10% of males

21% of females have moderate to severe levels of anxiety, compared to 9% of males

Data on suicidal thoughts shows that the highest rates of suicidal thoughts were among young women aged 18-24, with 37% of women in this age group reporting suicidal thoughts, compared to 17% of men.

This is reflected in presentations to mental health services, with services in Victoria reporting a significant increase in women presenting with serious mental health issues during COVID-19, including severe anxiety and depression.

Support and advocacy services are reporting that women who had previously been able to manage their mental health issues with medication and psychiatric support are no longer coping. Some examples include:

A major spike in demand for Australia’s only dual specialist clinic in women’s mental health at the Alfred Hospital – the service recorded 56 new referrals in one week in April, compared with an average of two new referrals per week, representing a 2800% increase in demand;

As of early May, almost all callers to the Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council’s advocacy line since COVID-19 restrictions began (the majority of whom are women) had disclosed suicidal ideation, which is extremely unusual and concerning.

While additional funding has been provided to frontline information services, such as Beyond Blue and Lifeline, there is a major service gap for those with pre-existing mental health conditions.

Increased family and sexual violence

Evidence suggests that the frequency and severity of family violence – including sexual violence – increases during emergencies, and increases are starting to be reported by services. Family and sexual violence can have significant negative impacts on women’s mental health, including anxiety and depression, panic attacks, fears and phobias, and hyper vigilance, as well as alcohol and illicit drug use, and suicide.

During COVID-19, there has been an increase in women presenting to mental health services who are at risk of or experiencing family violence, including a notable increase in women experiencing more extreme forms of violence and abuse and requiring emergency interventions involving police. There have also been reports in the community of women facing increased pressure regarding dowry payments which may put them at risk of violence.

Despite welcome funding injections for family violence response services, there are still limited pathways for mental health services to refer women to these expanded accommodation options.

All evidence points to higher rates of poor mental health as a result of COVID-19. Infographics courtesy of Gender Equity Victoria; view the full fact sheet here.

International students and migrant and refugee women

International students and migrant and refugee women are among those most severely impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. Many of these women are facing job loss and major financial stress, as well as isolation.

While some international students may be eligible to access the one-off payment announced by the Victorian Government, they are not entitled to federal government COVID-19 income support payments and are not eligible for Medicare. Migrant and refugee women also have limited access to healthcare and income support.

Blaming a foreign ‘other’ is a recurring narrative during pandemics, and there are increasing reports of people of Asian descent being subject to racist abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Exposure to racism is associated with poorer mental health outcomes. As frontline workers, particularly in health and retail, women of migrant and refugee backgrounds are particularly exposed to racist abuse and discrimination.

Older women

On top of fear and anxiety about contracting the virus, older women are more likely than older men to live alone or in residential care, meaning they are more likely to be isolated due to social distancing measures. Some family violence response services have reported an increase in calls from older people experiencing violence, including from adult children who have returned to their parents’ home due to job loss. At the same time, we have seen a resurgence of deep-seated ageist attitudes. While there is a lack of data that is both age- and gender-disaggregated, the intersection of ageism and gender inequality is likely to put older women at increased risk of negative mental health outcomes during COVID-19.

Women facing other social and economic challenges

COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on single mothers, who make up around 80% of single parent households. Employment of single mothers with dependent children is down 8% (compared with 5% for single fathers).[iv] Single mothers already face high rates of poverty, and financial hardship is a determinant of mental ill-health. Further distress is often caused by the eligibility requirements and compliance obligations for income support like mutual obligations.

COVID-19 has increased social isolation for women experiencing homelessness and placed additional pressure on women who were already struggling to support themselves and their children. Some of these women have reported that, although they were aware they could send their children to school (while it was closed) if they needed to, they were reluctant to do so as they didn’t want to flag to child protection and other government services that they were ‘not coping’.

Women with psychosocial disabilities who are in contact with the Victorian Mental Illness Awareness Council have disclosed increased harassment and bullying from the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) as they seek assistance with their plans.

Many other groups of women are also at increased risk for poor mental health at this time, including pregnant women and new mothers, women with disabilities, mental health carers, those who are managing other illnesses, and older women. Read our full policy brief for more details.

Recommendations for resilience and recovery

COVID-19 has both highlighted and intensified existing inequalities and gaps in Australia’s social support and mental health systems. It has drawn attention to the need for fundamental reform of these systems to ensure they effectively meet the needs of women and girls, and are resilient to respond to future emergencies, which – like COVID-19 – are likely to disproportionately impact women’s mental health.

We welcome the mental health funding announced by the federal and Victorian governments, together with the release of the National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan (Pandemic Response Plan) and the appointment of Australia’s first Deputy Chief Medical Officer for Mental Health. A range of positive measures have been introduced to respond to the mental health impacts of the pandemic – such as the expansion of telehealth – that should be retained as we move into the recovery phase and beyond.

It is encouraging to see that the Pandemic Response Plan recognises the link between family violence and women’s mental health. However, men but not women are recognised as a ‘vulnerable group’, despite clear evidence of poorer mental health outcomes among women, both during the pandemic and in general. The Plan does not recognise that the gendered social and economic inequalities that drive violence against women also directly drive poor mental health outcomes among women and girls, as illustrated in this Fact Sheet. For example, while the Pandemic Response Plan alludes to the role of the social security system in supporting mental health and wellbeing, it is silent on the need for ongoing access to adequate income support after the cessation of short-term measures, such as the higher rate JobSeeker payment. Nor does the Plan address the needs of mental health carers, other than in relation to bereavement support for suicide.

We welcome the focus in the Pandemic Response Plan on improving data and research, with more immediate monitoring and modelling of mental health impacts to facilitate timely and targeted responses across the spectrum of mental ill-health. The gendered inequalities outlined in this Fact Sheet highlight the importance of ensuring that all data collected is gender-disaggregated.

To better support women’s mental health during the COVID-19 response and recovery, we recommend that governments:

1. Apply a gender lens to the implementation of the Pandemic Response Plan, including collection of gender-disaggregated data and consideration of the specific social support and mental health needs of women and girls.

2. Address the gendered drivers of mental ill-health, including the social and economic inequalities that mean some groups of women are at greater risk of experiencing mental ill-health and/or experience financial and other barriers to accessing support, including:

Retaining free universal child care

Retaining the JobSeeker supplement and expanding the rate increase to other payment types including the Carer Payment

Providing immediate financial support to international students and other women on temporary visas who are unable to access income support and/or Medicare

Valuing the essential services provided by those working in the feminised health, social assistance and education sectors, including by increasing pay equity

Addressing gender norms and practices that harm women’s mental health, for example rigid gender stereotypes that underpin the division of household labour and the undervaluing of unpaid care work

3. Ensure the universal public health approach is gender-responsive, enabling women to access mental health information, online resources, helplines and support that best meet their needs, when and where they need it, including by resourcing both generalist mental health helplines and specialist agencies such as PANDA

4. Ensure there is enough capacity within the mental health system to manage the anticipated surge in demand for mental health support among women and girls as restrictions ease

5. Retain extension of the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) to cover telehealth consultations for mental health and increase access and affordability by increasing the Medicare rebate, as well as providing a diversity of support options for those unable to use telehealth

6. Expand the support available through Mental Health Treatment Plans under Medicare to address the anticipated increase in people needing support for mild to moderate mental health issues

7. Support perinatal mental health by expanding access to appropriate, affordable support services for women during pregnancy and after a baby’s birth

8. Create clear pathways to care for people with pre-existing mental health conditions who are not able to self-manage during the COVID-19 response and recovery, strengthening and making use of the full suite of outreach, community-based and home-based health and support options to prevent entry to acute care

9. Continue to strengthen the prevention of and response to family violence and all forms of violence against women, in line with the recommendations of the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence, as well as ensuring the mental health workforce is equipped to respond to women who have experienced gendered violence

10. Provide specialised and targeted mental health support for those experiencing compound trauma from multiple emergencies/disasters, such as bushfire and drought

11. Provide additional financial, practical and mental health support for carers

12. Improve the NDIA’s understanding of – and capacity to respond to – the needs of women with psychosocial disabilities.

NOTE: Read the October 2020 updated policy brief here: Women’s Mental Health in the context of COVID-19 and recommendations for action

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.

Posted by @SusanMaury

Notes

[i] The US study cited above by Adams-Prassl et al (2020) found that, while losing one’s job or having extra responsibilities did correlate with a decrease in mental health, this did not explain the negative effect on women’s mental health.

[ii] ANZ Research, 14 May 2020, based on ABS data.

[iii] The MAPrc online survey was open to the general public aged 18+ years; 29% of males and 39% of females identified that they have a current diagnosis of a mental illness. The preliminary analysis uses data collected between 3 April and 3 May 2020 and includes 1495 adults (81.6% were female). The over-representation of women in survey responses may itself be an expression of the anxiety and other negative mental ill health impacts experienced by women.

[iv] Analysis by Indeed, 21 May 2020, based on ABS data.