‘Citizen Joyce’, or the experiences of older single mothers in the welfare system

What can the recent dramas surrounding Barnaby Joyce tell us about progress for women’s equality on International Women’s Day 2018? In today’s post, popular welfare commentator Juanita McLaren (@defrostedlady) and Policy Whisperer Susan Maury (@SusanMaury), both of Good Shepherd Australia New Zealand, use the headlines as an opportunity to consider how the Coalition’s own policies on welfare would hypothetically impact on Mr. Joyce’s family were he not in politics.

We all know the statistics – 85% of single parent households in Australia are run by women. Women become single mothers for all kinds of reasons, sometimes as a consequence of circumstances completely out of their control. In previous blogs on the topic of single mothers, Juanita has written about conditionality of welfare, precarious work opportunities, financial insecurity, personal agency and the value of the unpaid work that mothers do – while also mulling over the overhead expenses involved in keeping single mothers in line.

When the unthinkable happens

In this blog we would like to look at a specific age group, one that is fast becoming one of our most vulnerable in terms of housing affordability, job security, long-term financial security, and the myriad number of systemic issues that come in later life. This is a time when unanticipated shocks may collide with a lifetime of being the primary carer, taking lower-paid flexible jobs, or having no paid employment at all. This can lead – possibly unexpectedly – to becoming a single mother just past the mid-point of your life.

Hypothetically, let’s say you are a woman who is 50 years old or thereabouts. You’ve been married for 24 years, agreeing to put your career on hold to support your husband’s business as the senior accountant in the large rural town where you’re raising your four beautiful children. Your husband is bringing in the average, quite comfortable senior accountant salary. Two of your children have moved away to go to university but you’re still sharing some of their expenses and you’ve got 2 remaining dependents, aged 15 and 17, in their last couple of years of high school. You own your own house, life’s going in the right direction.

Then suddenly, or perhaps in a clouded slow motion, your husband leaves you and it is revealed that he is also expecting a child with another woman. But you’ve put in all the hard yards! You’ve put off your career, where do you even begin when it comes to rebuilding? If the relationship ended poorly, your husband may decide that he doesn’t want to participate in the financial care of you or the children any more. First things first – you’ll need to explore your financial options.

No matter the reasons why women become single parents, poverty is the typical outcome. This is especially true for older women who have been out of the workforce. Photo credit: Pexels.

Running the numbers on welfare and child support – easier said than done

Given that your children are all over the age of eight, you’re not entitled to Parenting Payment Single. You’ll need to register for the Newstart Allowance ($170 less per fortnight than Parenting Payment Single) as an unemployed worker, as “mother of 20 years” is not considered a viable vocation in the welfare system. At the age of 50, and twenty years out of the workforce, you are in quite a precarious position with regards to having a consistent CV to draw from, and the teaching degree you earned 25 years ago before getting married and starting a family is way out of date, so you have to weigh up whether you have both the time and the money to become a registered teacher and then try to kick-start a teaching career. Other employment options are scarce, living in a rural town as you do.

Based on your former partner’s income, the standard Child Support formula shows that you will be entitled to an estimated $1135.17 in child support per month, which equates to $523 per fortnight. The day his new partner has their child, however, you can expect that amount to be reduced by between 25% and 33%, depending on how your two university-aged children are presented in the application, to about $392 as your former partner will now have a new dependent. Get ready to spend a while on the phone to the Child Support Agency however, as you will need to be the one to pull together all the facts about money being spent and the real costs of the children. That's quite a drop, and don't try arguing about the double income or even 1.5 income that your former partner may have access to in his new household. As a non-biological parent of your children, the new partner’s income is not considered when it comes to calculating the financial resources available to help support your children. Whilst you have been enabling your former partner's career by running his household and raising his children, his new family can now enjoy the fruits of his paid and your unpaid labour.

In Australia, 86% of Child Support recipients are women, and there are many options for the non-resident parent (usually the father) to reduce child support payments; the Child Support Australia website helpfully provides a list of legal methods to avoid paying child support. In cases where child support is not offered by the non-resident parent, it is the responsibility of the primary carer to initiate. This can include being actively encouraged to spy on your ex-partner to get evidence of hidden assets, for example, or unreported cash-in-hand work. It’s unfortunate that after the traumatic break-up of your long-term marriage, you are required to continue monitoring your ex-partner in order to make ends meet. This necessity is unlikely to keep the relationship civil moving forward, and will add undue stress if you choose this option. If the system appears to favour non-resident fathers – well, research indicates that it does.

Our current research into Single Mothers on Welfare to Work confirms these findings, as more than 50% of the women we have interviewed have chosen not to pursue Child Support due to the threat of re-occurring domestic violence and not wanting to engage with their ex partners for safety reasons. In other cases where the former partner has re-partnered and is now focused on his new family, it is often easier to keep the peace by allowing your partner to prioritise the new family by adopting an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ coping strategy regarding the former children. Any way you slice it, though, child support payments are both too low and too difficult to receive for single parents.

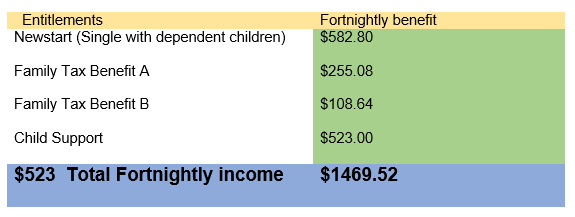

As a new single mother you punch in some figures to the Centrelink app – Age 50, two dependent children, no investments other than your home, no superannuation… and here is what you are entitled to:

$1469.52 per fortnight works out to $734.76 per week. That’s a drop from the $1082 that was coming into the household after tax when your husband was there - an annual decrease in income of $18, 056.48. When you consider economies of scale, and how much of your husband’s expenses were actually covered by his work, that’s a substantial decrease at a time when the teenage children are costing more in educational and general expenses – not to mention the two at university, who while not considered dependents are still highly dependent, and may be for some time.

Superannuation -?

You will be entitled to the superannuation that your ex partner earned in recognition of your marriage, however that process will also need to be initiated by you, and at your own expense, through a lawyer or via the overwhelming Australian Family Courts online system which again involves you acting as your own private detective.

Reinforcing patriarchal systems

While Barnaby Joyce has played a key role in creating another single mother in Australia, his vote record indicates he has not traditionally voted in favour of making things easier for single parents; he was for drug testing of welfare recipients and against housing affordability actions, for example. This piece explores how the Coalition Government’s approach to welfare would have directly impacted on his family should he not have chosen to go into politics, where members are protected from such humiliations as welfare support. The intention is not to wade into the debate about life choices, whether or not a politician's private life is our business, or debate abuse of power. Rather, it provides a good opportunity for reflecting on the punitive attitude the Coalition government takes towards single mothers – why they do so is not clear. This is a picture of what is a reality for many Australian women who live outside the bubble of the privileged, wealthy, male-dominated Australian government – a government that writes policy and is gradually tightening the screws on the lives of regular Australian women who don't have access to an expense account and often don't have the financial means or even the personal safety required to make a smooth transition from married life to single parenthood.

It is the case that two-thirds of our lawmakers are men, and, as the Joyce family readily admitted in an interview published a year ago, the demands of the role are such that Barnaby was home as little as one day per month. These unrealistic time demands make it very difficult for women with caring responsibilities to serve in Parliament – as, also one year ago, Jamila Rizvi explains in light of Kate Ellis’ resignation due to family pressures. In other words, it appears that the same politicians who vilify single mothers are also enabled in their demanding careers by unpaid (or in some cases underpaid) partners or female workers who assume gendered child care and home duties roles in order to sustain their life in politics.

Australia’s welfare policy is becoming more and more punitive, more conditional, and in many cases actions are mandatory but poorly matched to the needs of the individual. For example, current policy states that unpartnered mothers need their relationship status verified by a third party, in order to qualify for parenting payment single. (A requirement that adds insult to injury in the case of ‘Citizen Joyce.’) This Coalition policy is either deliberately complicating the process, or assumes that ‘women like this’ are untrustworthy bludgers; perhaps a bit of both. Meanwhile, single mothers’ time is filled by performing approved activities through a Job Active service provider, from volunteering to applying for a designated amount of jobs regardless of their suitability or long-term potential.

Barnaby Joyce himself has been quoted as telling unemployed people to “get off your backside” and find a job, declaring that working Australians should not fund welfare payments for those not willing to “have a go”[i]. His ongoing support of drug testing shows both his lack of understanding regarding issues of addiction and a lack of interest in utilising an evidence base in policy formulation. Similar policies in other countries have been found to be both expensive and unnecessary, in part because welfare recipients appear to have fewer substance abuse issues than the general population. However, if the goal is to humiliate welfare recipients such as ‘Citizen Joyce,’ then the policy is on target.

It is time for our social security policy to stop blaming people for struggling to make ends meet - a situation that our own government is exacerbating through increasingly punitive and conditional welfare. Regardless of the reasons why a woman becomes a single parent, there is no excuse to strip her of her rights and dignity, and force her and her children into desperation and poverty. Government welfare policy seems deliberately designed to make life as difficult as possible while vilifying and blaming single mothers for their situation, despite the benefits that the majority of Australian lawmakers receive from women in their gendered, unpaid and/or underpaid roles.

At one level, the story of Barnaby Joyce is a personal, sad story of relationship breakdown. But it is also reflective of a government which is interested in reinforcing and upholding patriarchal structures, which values women based on their utility to men, and believes it is justified in punishing women when they are no longer filling this role.

Many thanks to Kay Cook (@KayCookPhD) who assisted with this piece.

[i] Coalition regional MPs target ‘job snobs’, The Australian, 21 April 2017.

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.