Building Inclusive Police Organisations: How Do Women Experience Gender Equity Policies?

While women have made great strides in male-dominated industries, representation is seldom adequate to shift organisational culture, particularly in highly masculinised industries. In today’s analysis, Kathy Newton (@KathyNewton2208) of Western Sydney University (@WesternSydneyU) shares her findings in how female police officers experience three policies designed to improve gender parity: the provision of breastfeeding rooms, flexible or part-time work options, and gender quotas. This analysis is drawn from a recently-published article.

A long history of policing for women

Women have been serving as sworn officers in Australian Police Organisations since 1915 (you can read a comprehensive history here). From humble beginnings, they have made great strides and are now represented in all areas of policing. There are even two female commissioners of police: Katrina Carroll has led the Queensland Police Service since 2019, and Karen Webb is newly appointed to the New South Wales Police Force. Despite this public perception of success, many policewomen, and more specifically policewomen who are mothers, experience a hidden reality of discrimination, sexual harassment, and marginalisation.

There are well-established Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) policies and initiatives currently in place in all Australian police organisations. Many of these policies are considered ‘family friendly’ and have been designed and implemented specifically to assist policewomen once they become mothers. However, perceptions of their effectiveness are mixed; both the executive and the policewomen who they are intended to help have varied perspectives on these policies and initiatives. Examples of these mixed perspectives are reported in my recently published qualitative research examining motherhood and policing careers. The policewomen I interviewed raised the issues of the underutilisation of breastfeeding rooms, their experiences when trying to access part-time/flexible arrangements and their concerns regarding quotas.

Breastfeeding Rooms in Police Stations

The introduction of breastfeeding rooms by one large police organisation was applauded by the Australian Breastfeeding Association. The rooms are a relaxed and private area where lactating mothers can express and store milk. The initiative portrays a police organisation that is serious about gender equality and is taking steps to remove structural barriers that make it difficult for policewomen. However, the underlying reality is that these rooms are not often used by policewomen for fear of disparagement from their male colleagues.

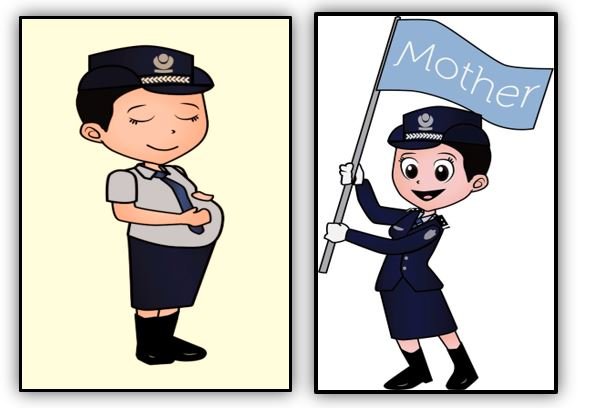

While police women are now commonplace, they are often expected to leave their parenting responsibilities at the door. Gender equity policies are designed to change that, but culture change is lagging behind. Illustrations by Beth Larkin.

While it is assumed that many policewomen stop breastfeeding prior to returning to work, those that do not are still reluctant to use the breastfeeding rooms. Despite a formal policy that allows them to take time out from their work to express, policewomen feared they would be stigmatised if they did so. Women said that secretly lactating in the ladies’ bathroom was a preferable alternative to being criticised by male work colleagues. Therefore, despite a formal breastfeeding policy, the informal occupational culture has a more powerful influence on policewomen. Occupational culture often undermines attempts at organisational change and maintains structural practices that generate inequality.

Part-Time and Flexible Work

There is conflict between the traditionally masculine culture of policing and the modern reforms aimed at creating a flexible work environment, which assists police mothers to manage their work-life balance. While all Australian police organisations have good part-time and flexible work policies, they are not always effective. Police mothers who attempt to take advantage of these policies often face resistance and hostility. One common practice requires police officers who take up the option of part-time hours to relocate to an administrative or other “female friendly” position in the workforce. In these sections, they often find the work tedious and boring, their qualifications and skills lay dormant, and opportunities for promotion are limited. This type of organisational decision making creates a gendered pattern of jobs, because most part-time workers are women. The research found that occupational culture labels these types of jobs as not ‘real policing’ and part-time workers are often considered as being only partly committed to their work. Consequently, this reinforces the gendered hierarchy between men and women.

Another area of difficulty policewomen found was negotiating part-time work with their supervisors. Officers working full-time but requiring flexible hours due to childcare responsibilities also found it difficult. While the policies allow for part-time/flexible hours there is a loophole that indicates that the final decision is at the discretion of their commander. The research found that if the commander is supportive and amenable to part-time/flexible arrangements policewomen tend to have better experiences. However, many commanders are still influenced by traditional police culture and are not sympathetic towards policewomen exercising their rights. Consequently, part-time/flexible arrangements are often understood by policewomen as an option in exchange for sacrificing their career aspirations. The policewomen I spoke to were disgruntled by this duality and wanted their police organisations to be more flexible.

Gender Quotas

Independent inquiries into sexual harassment and discrimination were conducted into Victoria Police in 2015, and South Australia Police and the Australian Federal Police in 2016. As a result of the findings, a number of reforms were implemented to rectify discrimination, including the use of quotas to increase the number of policewomen being promoted. Quotas are a swift and effective approach for addressing inequality and creating rapid change. However, a by-product of implementing quotas can be intense resistance from workers, which gives rise to adversarial and hostile work conditions.

The research indicated that many policewomen were experiencing blowback from their male officers. This conflict was unpleasant, and what most upset the policewomen is that their promotions were not viewed as merit based. Hence, they were seeking strategies and justifications to counter these negative views. Some strategies involved adopting a professional attitude and ignoring the criticism, having confidence in their competence and ability, and recognising the importance of having women in managerial positions.

What needs to happen next

The overarching finding from this research was that, while the policies may be good, they often failed to be successfully implemented in such a way that women benefited as intended. Their failure is attributed to the masculinised occupation cultures of police organisations (see also here and here), which are opposed to change. In policing there is a deep-seated focus on masculine identity, which excludes women. When policewomen become mothers, their stigmatisation is compounded because motherhood is associated with femininity, which is the antithesis of a masculine crime-fighter.

The study shows that policewomen are not convinced that they obtain much assistance from EEO policies and initiatives. When they do obtain benefits from EEO policies, which helps them to succeed in their careers, they think it is due to luck rather than their legal entitlement. Two suggestions were put forward as options to assist policewomen obtain benefits from EEO policies and initiatives. The first was to have an independent arbitrator to negotiate decisions on flexible and part-time work arrangements. This would reduce hostility between the workers and managers. Furthermore, decisions need to be resolved expeditiously to avoid stress. A further suggestion is that police organisations should focus on childcare solutions, making this an organizational issue as opposed to a problem for individual women. One response could be providing childcare facilities that are connected to police stations.

Overall, the research revealed that policewomen believe that EEO policies and initiatives only have a cosmetic effect that allow police organisations to promote themselves as equal opportunity employers. Despite 30 years of gender equity legislation, policewomen, particularly those that are mothers, are still marginalised and discrimination remains an ongoing issue.

References

You can read more about this research when the author’s forthcoming thesis is published: Newton, K 2022 Flying the mother flag: gendered Institutions and the lived experiences of police mothers in Australia, thesis, Penrith, Western Sydney University, viewed 15 April 2022, Research Direct database

Read related content:

This post is part of the Women's Policy Action Tank initiative to analyse government policy using a gendered lens. View our other policy analysis pieces here.

Posted by @SusanMaury