COVID-19 fuels global health tensions

In this post, Dr Belinda Townsend from ANU (@BelTownsend) says Australia can play a greater role in supporting mechanisms for affordable access to new treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. This piece was originally published on the East Asia Forum as part of its special feature series on the novel coronavirus crisis and its impact, prior to the 73rd World Health Assembly.

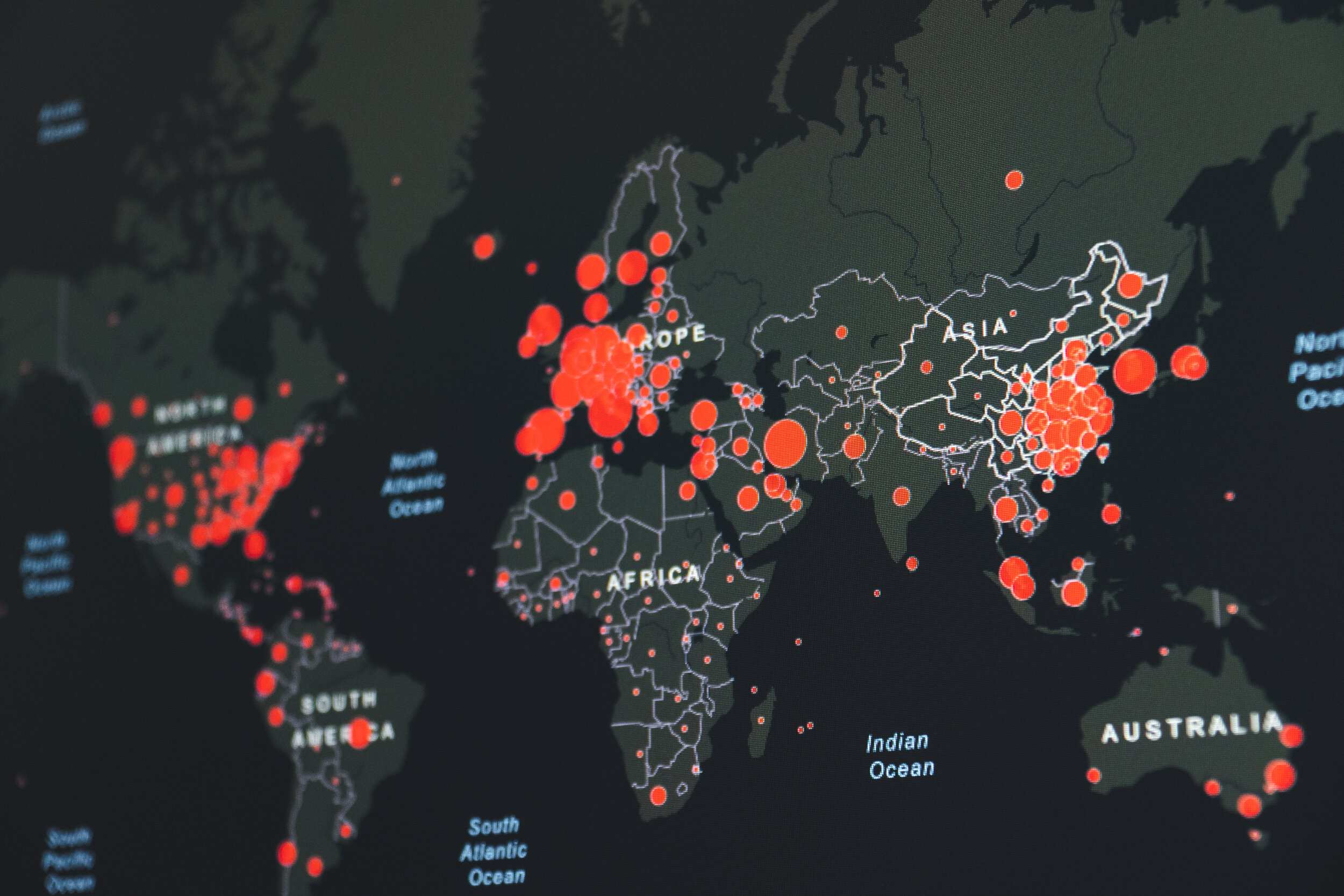

As of 10 May over four million COVID-19 cases had been reported worldwide, with 280,000 confirmed deaths. The pandemic has highlighted the need for strong national health systems and regional infectious disease monitoring. Rising global health tensions urge the need for governments to prioritise international mechanisms that promote affordable access to new treatments and vaccines.

As China reports fewer cases of COVID-19, it is seeking to portray itself as a global health leader by supplying medical experts, equipment and resources overseas. Chinese President Xi Jinping has expressed China’s ambition for a ‘Health Silk Road’ with partner countries of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). On 21 March China sent 100,000 medical masks and 776 protective suits to Spain via existing BRI railway infrastructure.

China’s Health Silk Road has its origins in a 2015 three-year plan for health cooperation as part of its broader BRI agenda. The original plan included establishing health cooperation mechanisms between BRI countries and projects for infectious disease prevention and treatment. The plan was supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) which entered into a strategic partnership with China in early 2017 ‘to target vulnerable countries on the Belt and Road and Africa’. But despite signing numerous bilateral cooperation agreements with Silk Road countries, there is little to show for it yet.

China’s moves to reassert the Health Silk Road in response to COVID-19 reflects an attempt at reframing the country’s image — from the source of the virus to being a good international citizen. However, this has been met with increasing criticism by the United States, which has alleged that China delayed reporting on the severity of the virus to stockpile medical equipment.

The WHO has also become embroiled in US-China tensions. On 14 April, US President Donald Trump launched an attack on the WHO’s handling of the virus and announced a funding freeze pending review. Two weeks later, US officials presented G7 partners with a list of reforms it wanted the WHO to make. More recently, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed that the US has proof that the virus originated from a laboratory in China. The WHO and the wider intelligence community have reported that there is no evidence to substantiate these claims.

These US criticisms of the WHO and China have coincided with the United States becoming the country with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths, amid global criticism for its own slow response to testing, treatment and prevention. A leaked US Republican Party memo reveals that shifting the blame is an explicit party strategy.

Trump’s attack on the WHO is a significant concern for the future of global health. The United States is the WHO’s largest donor, contributing 14.67 per cent to its 2018–2019 budget. By withholding funding from the organisation tasked with helping countries to contain the pandemic, this decision could cost lives. Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of the prestigious medical journal The Lancet has gone further, labelling Trump’s decision ‘a crime against humanity’.

The funding freeze also reveals deeper issues regarding the organisation’s control over funding. The WHO has become more reliant on voluntary contributions from rich member states and global health partners — the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is its second-biggest funder — which are often tied to donors’ pet projects. Assessed contributions (amounts paid by each member state calculated by wealth and population) are not tied to specific donors’ projects, but they have fallen to less than 25 per cent of the budget due to a longstanding freeze on payments levels.

This means that the WHO has less power to direct where money is spent and, as a consequence, some important health issues such as addressing the social determinants of health are underfunded. Public health groups have long called for an increase in member states’ assessed contributions to provide more flexible funding that can be directed where it is needed. Now is not the time to cut funding.

Another emerging tension is the question of who pays and who can access new treatments and vaccines for COVID 19. This reflects longstanding battles over the rules and norms governing pharmaceutical research and development and debates about mechanisms to enable low- and middle-income countries to affordably access treatments. In the context of COVID-19, public health groups have intensified calls for mechanisms that ensure equitable and affordable access to vaccines and treatments when they become available.

One such mechanism recently proposed by the Costa Rican government is a voluntary ‘pool’ for sharing rights to technologies for the detection, prevention, control and treatment of COVID-19. The proposal would create a voluntary ‘pool’ of monopoly rights (such as patents and regulatory test data) for tests, vaccines and diagnostics, with either free access or licensing ‘on reasonable and affordable terms, in every member country’.

The proposal has received support from over 150 public health and civil society organisations as well as the European Union. On 6 April, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus also voiced support for the mechanism, stating that the WHO was ‘working with Costa Rica to finalise the details’.

It is perhaps a coincidence that Trump’s announcement to withhold funding from the WHO came eight days later. But the United States has a long, documented history of pressuring other countries to introduce rules to extend monopolies for pharmaceuticals. The potential costs of a vaccine in the United States is being hotly debated, with some politicians pointing to pharmaceutical industry lobbying to prevent price restrictions on a new vaccine.

Notably, the United States did not contribute any funds to a recent virtual fundraising summit hosted by the European Union, where Australia offered AU$352 million (US$226 million) of public funds towards vaccine development.

In exchange for this significant public expenditure on vaccine and treatment, governments must voice support for mechanisms that promote affordable access, like Costa Rica’s proposal for a voluntary pool of rights. Australia could play a greater role in the region in this regard by voicing support for the voluntary pool at the World Health Assembly in late May.

___

The author Belinda Townsend is a Research Fellow at the School of Regulation and Global Governance and Deputy Director of the Menzies Centre for Health Governance at the Australian National University.

Content moderator: Sue Olney